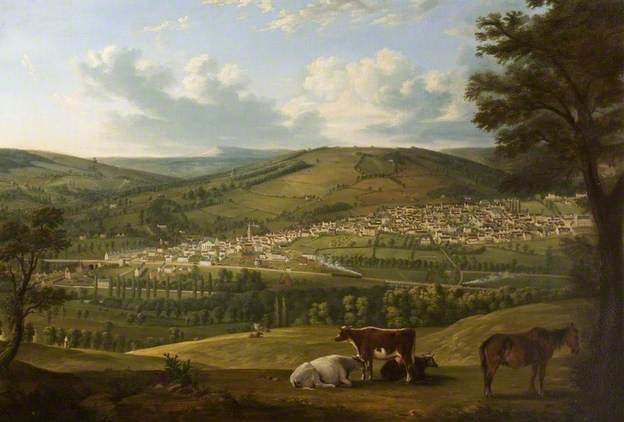

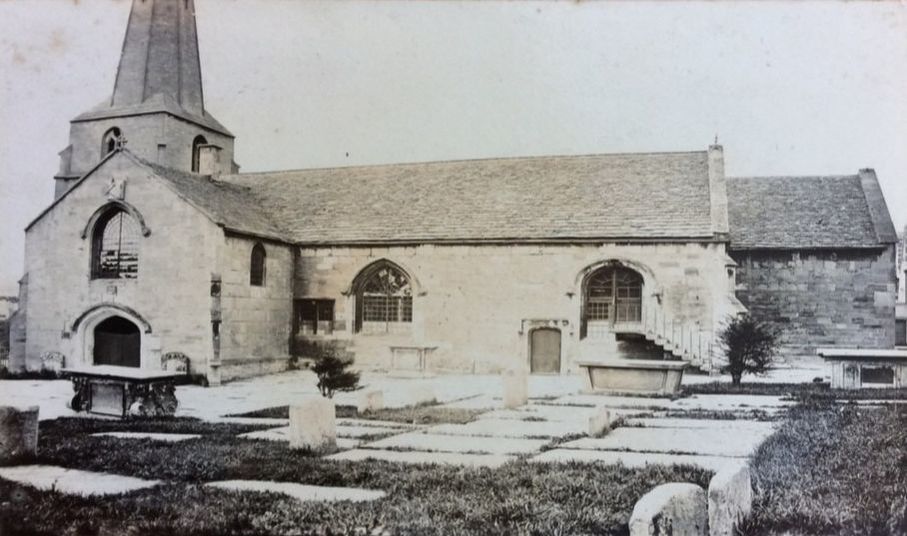

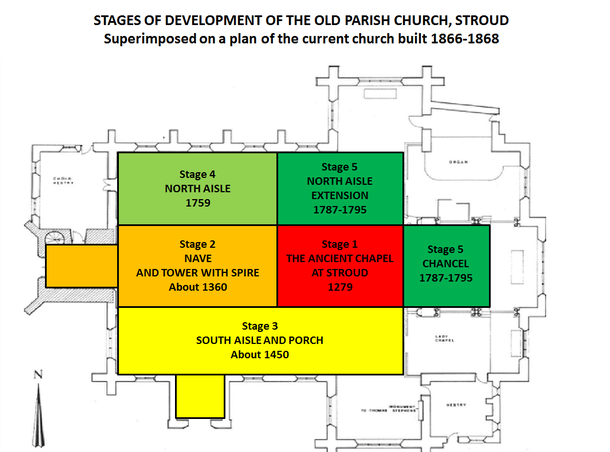

The site has been a place of worship for over 700 years at least. In 1866, the Victorians felt that the existing building could no longer meet the growing demands of the town of Stroud, and rebuilt the church (except for the 14th Century tower and spire). The building was consecrated by the Bishop of Gloucester in 1868 – so in 2018 we celebrated the 150th anniversary of the ‘new church’. Here, we take a look back at our history, starting with the original church.

The Origins of the Church

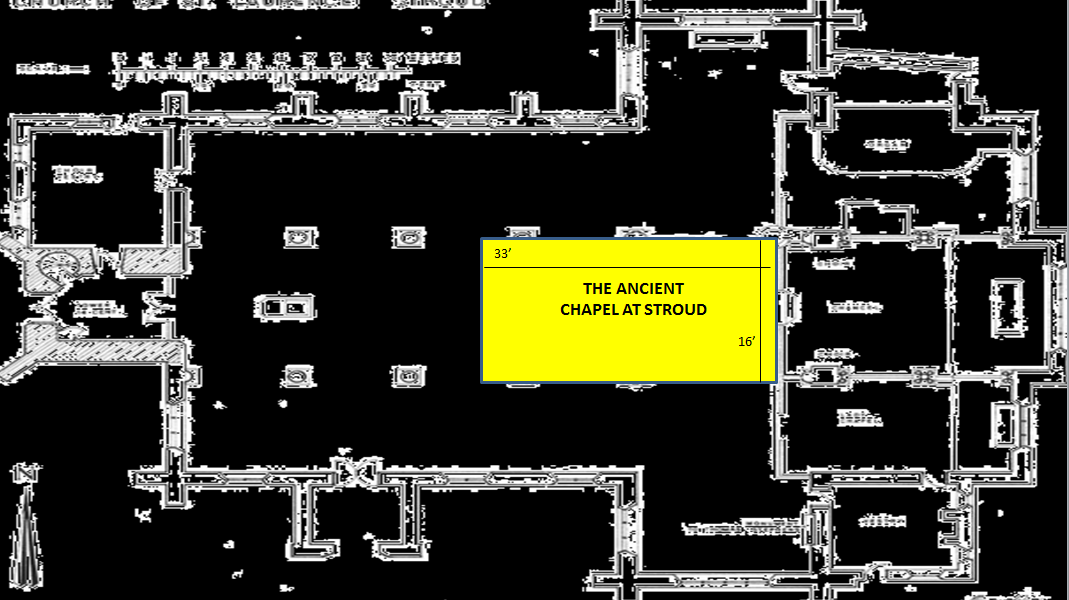

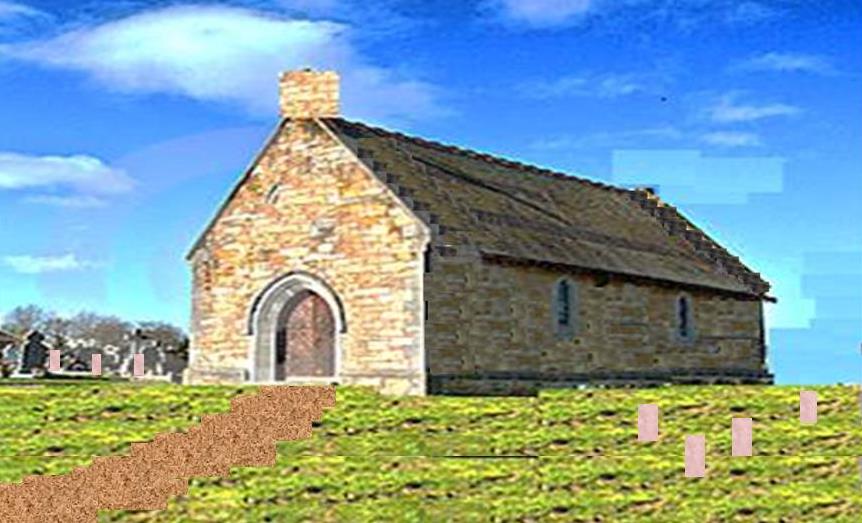

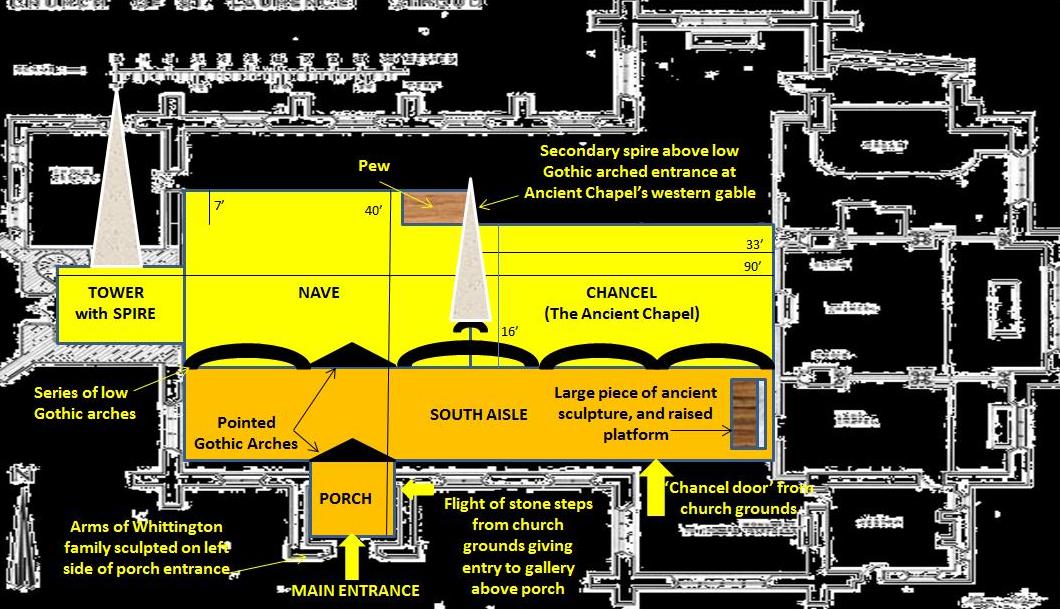

It has been suggested that there may originally have been either a Saxon church or one of early Norman origin on the site of the current church, but the first documented evidence is of an ancient chapel dating from 1279. This medieval church was a small, simple stone building, probably with a bare earth floor, measuring just 33 feet by 16 feet and built on an east–west access, with an arched entrance at its western end. At that time, the building acted as a chapel of ease to its mother church in the then much bigger settlement of Bisley, and served the surrounding scattered dwellings and farmsteads of the area before the town of Stroud was to emerge.

It has been suggested that there may originally have been either a Saxon church or one of early Norman origin on the site of the current church, but the first documented evidence is of an ancient chapel dating from 1279. This medieval church was a small, simple stone building, probably with a bare earth floor, measuring just 33 feet by 16 feet and built on an east–west access, with an arched entrance at its western end. At that time, the building acted as a chapel of ease to its mother church in the then much bigger settlement of Bisley, and served the surrounding scattered dwellings and farmsteads of the area before the town of Stroud was to emerge.

LEFT The Ancient Chapel of Stroud, superimposed on a plan of the church as it is today;

RIGHT Reconstruction of what the ancient chapel might have looked like

RIGHT Reconstruction of what the ancient chapel might have looked like

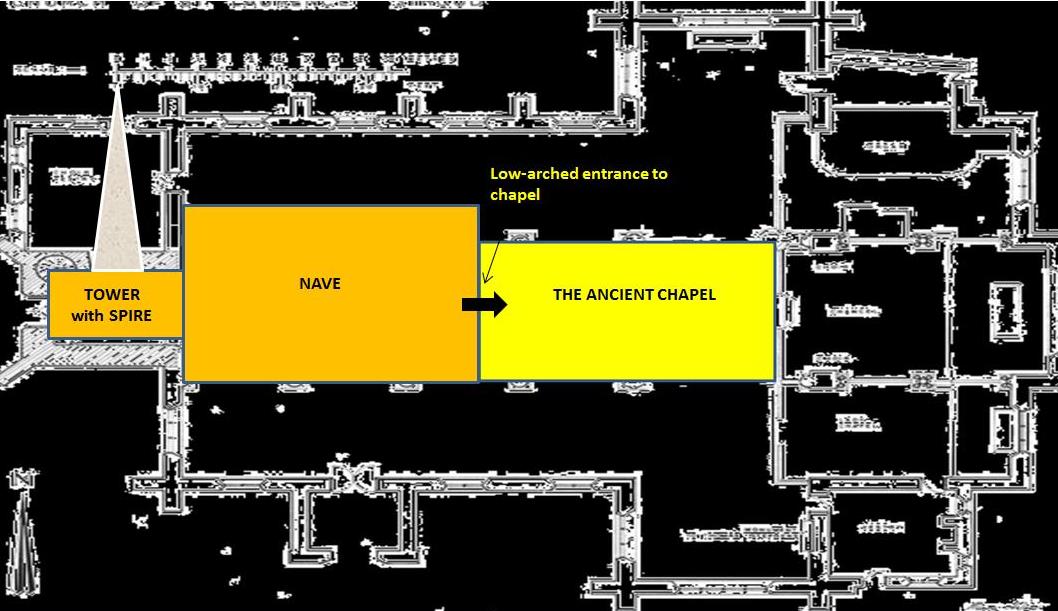

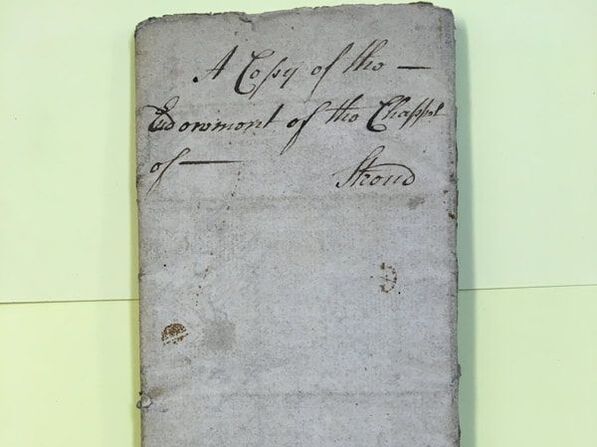

Deed of Composition

The origins of the town of Stroud effectively date from 29th July 1304, when a Deed of Composition was signed between William, vicar of the mother church at Bisley, and his rectors Henry Avery and Robert le Eyre, and the inhabitants of Stroud, represented by Thomas of Rodeborowe, William Proute, Henry of Monemuwe, Nicholas le Seymour and Henry le Fremer, giving them the responsibility for the upkeep of the chapel (whose chancel was already in a derelict state), and for supporting the appointment of a resident chaplain of their own with responsibility for Over (Upper) and Nether (Lower) Lypiatt, Stroud, Paganhill and Bourne. In order to provide an income and rents to support this now independent chapel, it was assigned land to the south of the church then known as Pridie’s Acre – later becoming today’s The Shambles. In 1307, Edward II came to the throne as King of England. He was overthrown in 1327 as a result of a plot by his wife, Isabella of France, and her lover Roger Mortimer, and was incarcerated at Berkeley castle, where he was probably murdered later that same year. Edward was buried in Gloucester Cathedral where his body and tomb lie today. A small spire or turret was erected over the west door of the ancient chapel shortly after the accession of Edward III in 1327. In about 1360, a nave was added to the existing chapel, and a large tower and spire built at its western end. That tower and spire, of local limestone, are all that survive today of the original 14th century building.

The origins of the town of Stroud effectively date from 29th July 1304, when a Deed of Composition was signed between William, vicar of the mother church at Bisley, and his rectors Henry Avery and Robert le Eyre, and the inhabitants of Stroud, represented by Thomas of Rodeborowe, William Proute, Henry of Monemuwe, Nicholas le Seymour and Henry le Fremer, giving them the responsibility for the upkeep of the chapel (whose chancel was already in a derelict state), and for supporting the appointment of a resident chaplain of their own with responsibility for Over (Upper) and Nether (Lower) Lypiatt, Stroud, Paganhill and Bourne. In order to provide an income and rents to support this now independent chapel, it was assigned land to the south of the church then known as Pridie’s Acre – later becoming today’s The Shambles. In 1307, Edward II came to the throne as King of England. He was overthrown in 1327 as a result of a plot by his wife, Isabella of France, and her lover Roger Mortimer, and was incarcerated at Berkeley castle, where he was probably murdered later that same year. Edward was buried in Gloucester Cathedral where his body and tomb lie today. A small spire or turret was erected over the west door of the ancient chapel shortly after the accession of Edward III in 1327. In about 1360, a nave was added to the existing chapel, and a large tower and spire built at its western end. That tower and spire, of local limestone, are all that survive today of the original 14th century building.

LEFT The addition of the nave and tower and spire, about 1360;

RIGHT Carved stonework from the original church (now in St John's Church, Stroud, News South Wales, Australia)

RIGHT Carved stonework from the original church (now in St John's Church, Stroud, News South Wales, Australia)

The Dick Whittington Connection

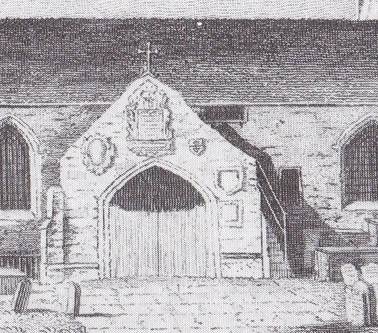

As successive famine, plague and wars ravaged England during the medieval period, there are no surviving records relating to the church during most of the 1300s. Then in 1395, Richard ‘Dick’ Whittington, the celebrated Mayor of London, came into possession of Over (Upper) Lypiatt Manor (today Lypiatt Park). On Richard’s death it passed to his brother Robert, and was to remain in the hands of the Whittington family through to the end of the 15th century. During that time they endowed the church with much property and funds, and in about 1450 helped pay for the addition of a south aisle and porch. These lay almost exactly where today’s south aisle and porch are (the Victorian’s used the same foundations when they rebuilt the church), and the church still has in its possession the original Whittington family stone with its coat of arms which originally adorned the porch. Richard’s grandnephew Thomas is believed to have been buried under the south aisle upon his death in the 1490s. It was during this time that the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485) were fought between the Houses of York and Lancaster for the throne of England.

As successive famine, plague and wars ravaged England during the medieval period, there are no surviving records relating to the church during most of the 1300s. Then in 1395, Richard ‘Dick’ Whittington, the celebrated Mayor of London, came into possession of Over (Upper) Lypiatt Manor (today Lypiatt Park). On Richard’s death it passed to his brother Robert, and was to remain in the hands of the Whittington family through to the end of the 15th century. During that time they endowed the church with much property and funds, and in about 1450 helped pay for the addition of a south aisle and porch. These lay almost exactly where today’s south aisle and porch are (the Victorian’s used the same foundations when they rebuilt the church), and the church still has in its possession the original Whittington family stone with its coat of arms which originally adorned the porch. Richard’s grandnephew Thomas is believed to have been buried under the south aisle upon his death in the 1490s. It was during this time that the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485) were fought between the Houses of York and Lancaster for the throne of England.

Paul Hawkins Fisher wrote in his “Notes and Recollections of Stroud” of 1871 that: “… the arms of the Gloucestershire family of the Whittingtons are stated, generally, to be only a fesse of two lines checky; though sometimes they bear three or four such lines, having an annulet in the right corner of the shield. The arms on the porch, however, had a fesse with two lines checky, between two crescents, without the annulet; but the repetition, in base, of the crescent in chief, as a mark of cadency, is supposed to be an error of the sculptor.” The existing stone precisely matches Fisher’s description, with a checked band of two lines running across the centre of the shield (‘a fesse of two lines checky’, in heraldic terms), lying between two crescents. The ‘mark of cadency’ that Fisher refers to is a device in heraldry used to distinguish between different male members of a particular family. The crescent is usually designated for the second son born. The mark of cadency would normally be added solely ‘in chief’, i.e. at the top of the shield. Richard ‘Dick’ Whittington, the celebrated mayor of London, came into possession of Over (Upper) Lypiatt Manor in 1395, as settlement for a debt owed to him by his uncle Philip Maunsell. On Richard’s death, without heir, in 1424 it passed to his brother Robert Whittington, and subsequently to Robert’s son Guy, and then Guy’s son Thomas, before coming into the possession of the Wye family. Robert Whittington was the second son of Sir William Whittington, which may explain the crescent mark of cadency on the arms on the stone. The stone was at some time built into the wall of the old boiler house under the vestry (which was probably the entry to the family vault), and was for many years covered by an electricity switchboard before being rescued.

|

The original 1304 Composition of the Chapel of Stroud was exemplified and confirmed in the year 1493. This copy of that further endowment, made in 1734, comes from the Will Trust papers of George Byng MP of Wrotham Park in Hertfordshire, and has been kindly supplied by Wrotham Park archivist, Charles Dace.

|

The layout of the church by about 1500

Protestant Martyr

The 1500s were a time of much upheaval for the Church in England. In 1517, Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg, Germany, thus effectively starting the Reformation; and in England, Henry VIII’s dynastic ambitions had led to the break with the papacy in Rome in 1534. The earliest existing records of curates at Stroud during this period hint at the turmoil affecting the parish and its clergy. In March 1540, Anthony Parsons, a former friar and then curate at the church, was imprisoned in Gloucester Castle having been reported to Thomas Cromwell for 'ill preaching‘. He was sent to Windsor to be examined concerning heresy by the bishop of Salisbury, and was subsequently condemned to be burnt at the stake. John Foxe, in “Foxe’s Book of Martyrs” first published in 1563, records that upon being brought to the stake, Parsons asked for a drink which he drank to his fellow sufferers with the words, "Be merry, my brethren, and lift up your hearts to God; for after this sharp breakfast I trust we shall have a good dinner in the Kingdom of Christ, our Lord and Redeemer“.

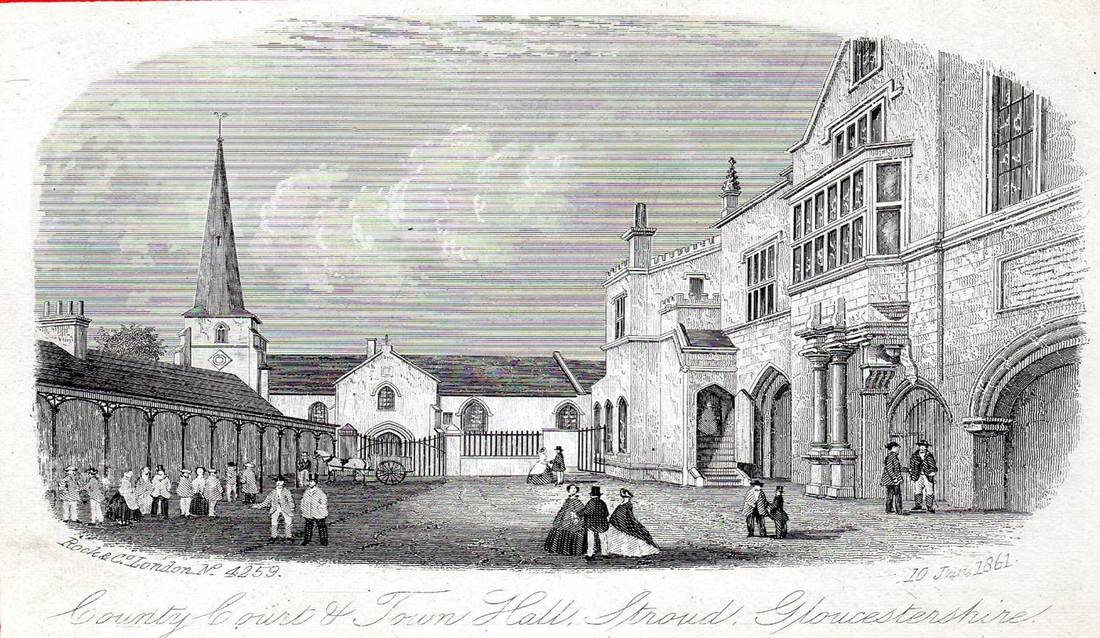

Under Elizabeth I’s Act of Uniformity of 1559, only a new Book of Common Prayer was to be used in parish churches, and Catholic Mass became illegal. Meanwhile, the town of Stroud continued to grow during the period, and by 1563 the estimated population of the parish had risen to 130 households, and a trading area had begun to build up around the church in what is now known as The Shambles, The Cross, and High Street. Around 1590, John Throckmorton, the then Lord of Over (Upper) Lypiatt Manor, built a Market House here – now known as the Old Town Hall.

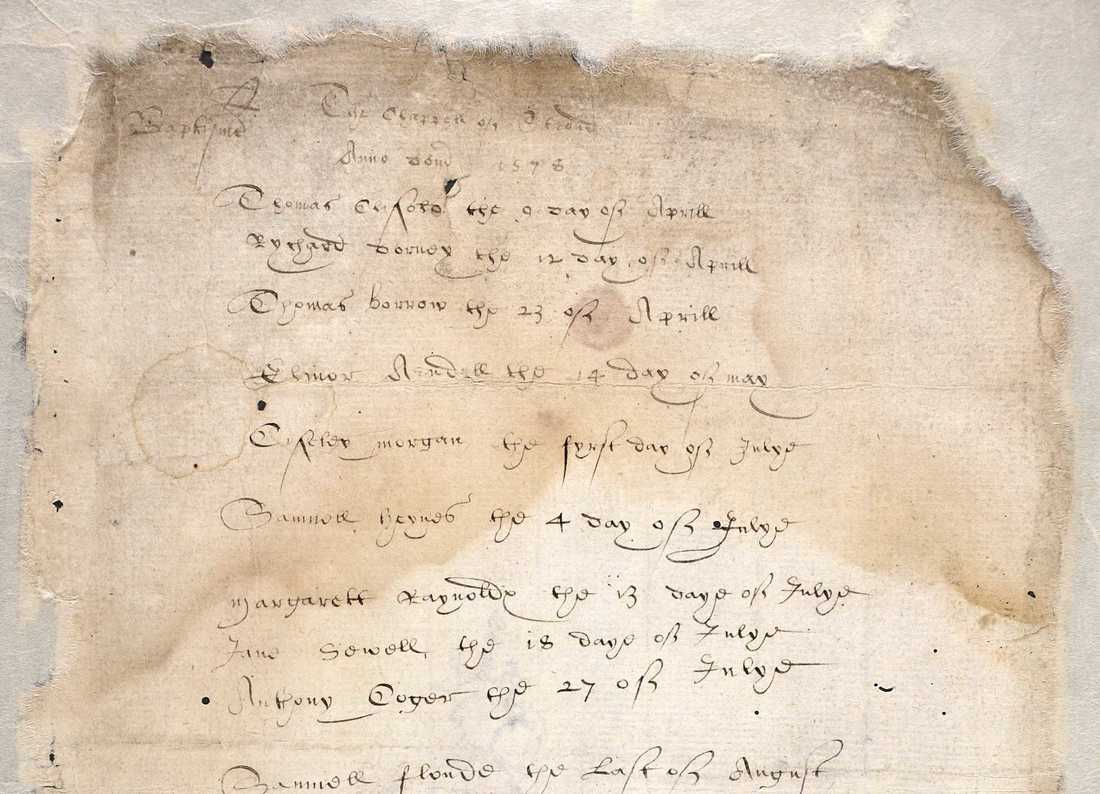

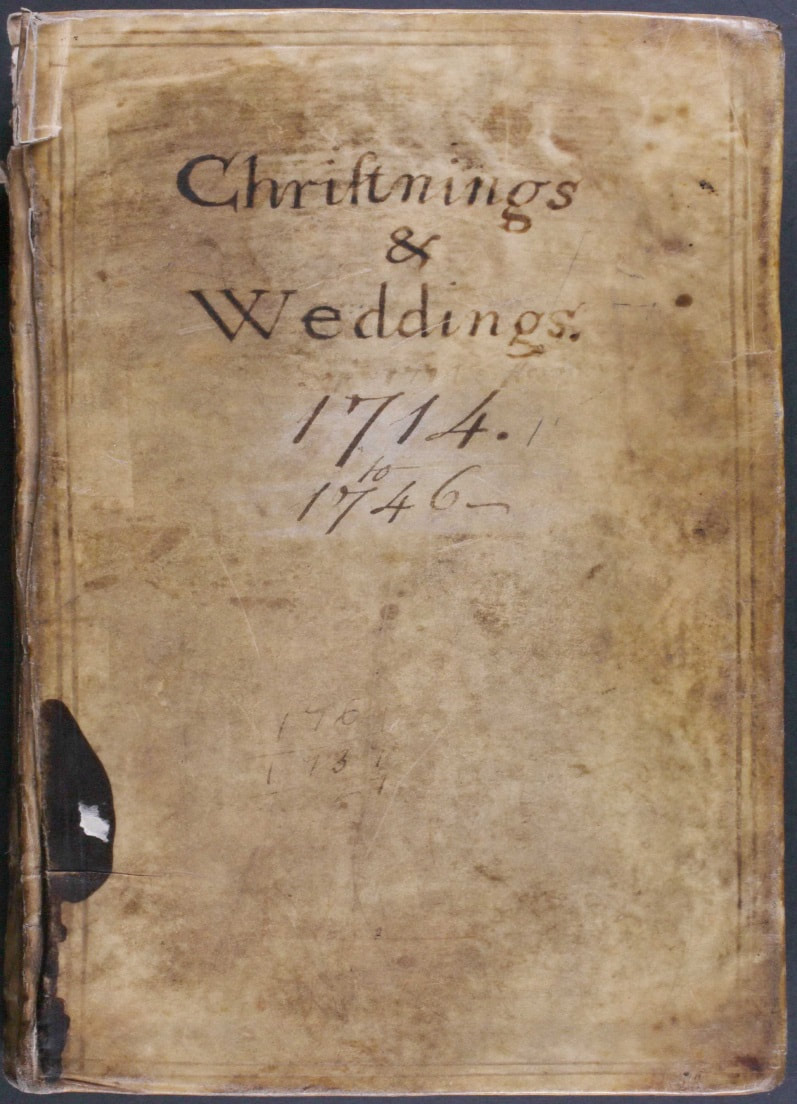

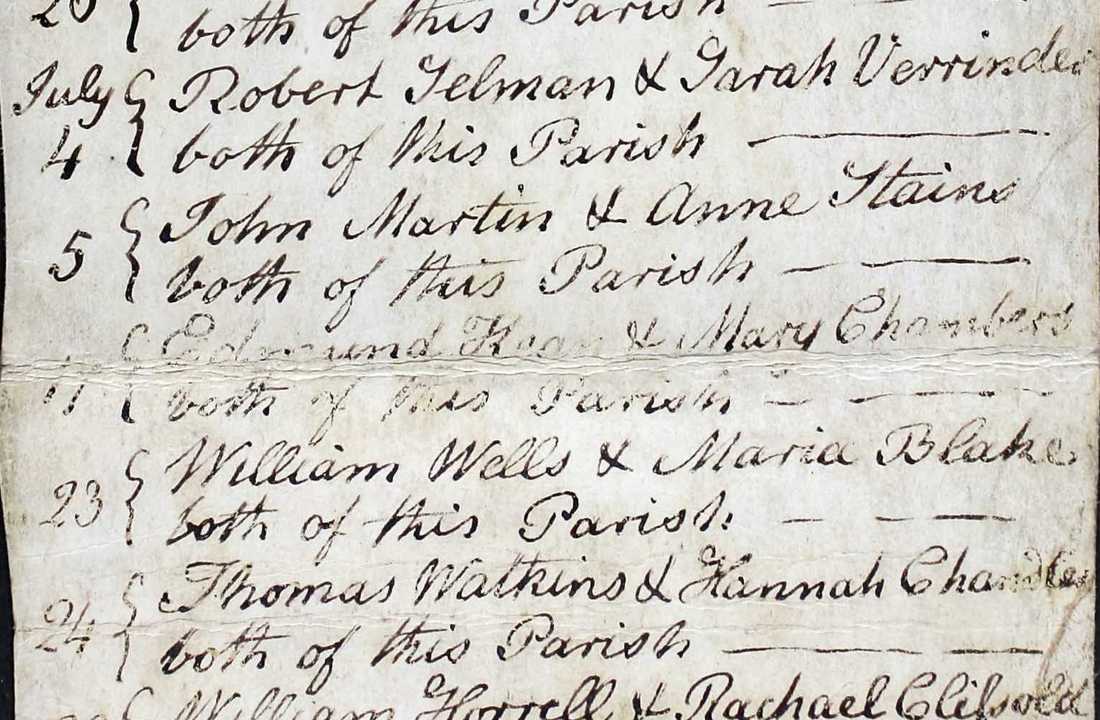

The Earliest Parish Records

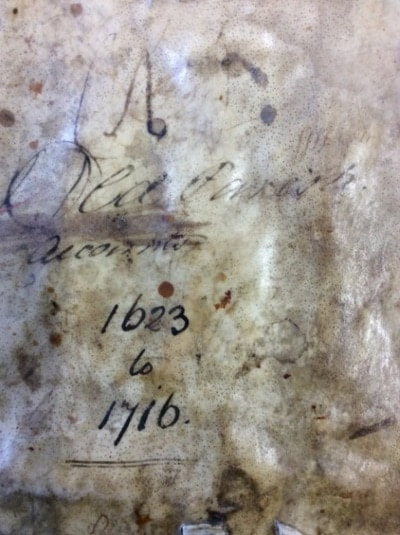

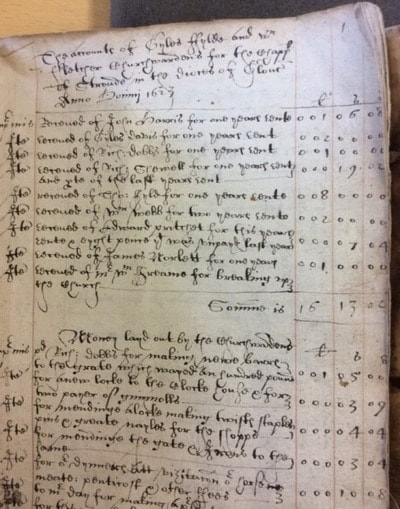

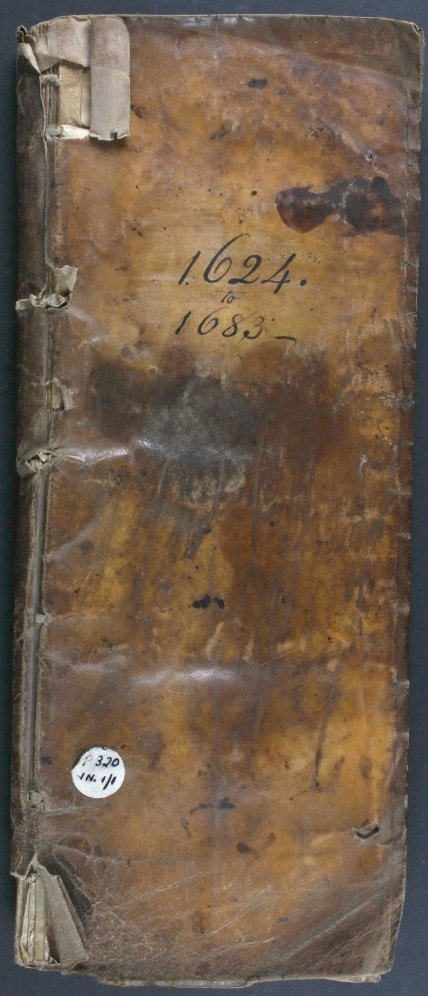

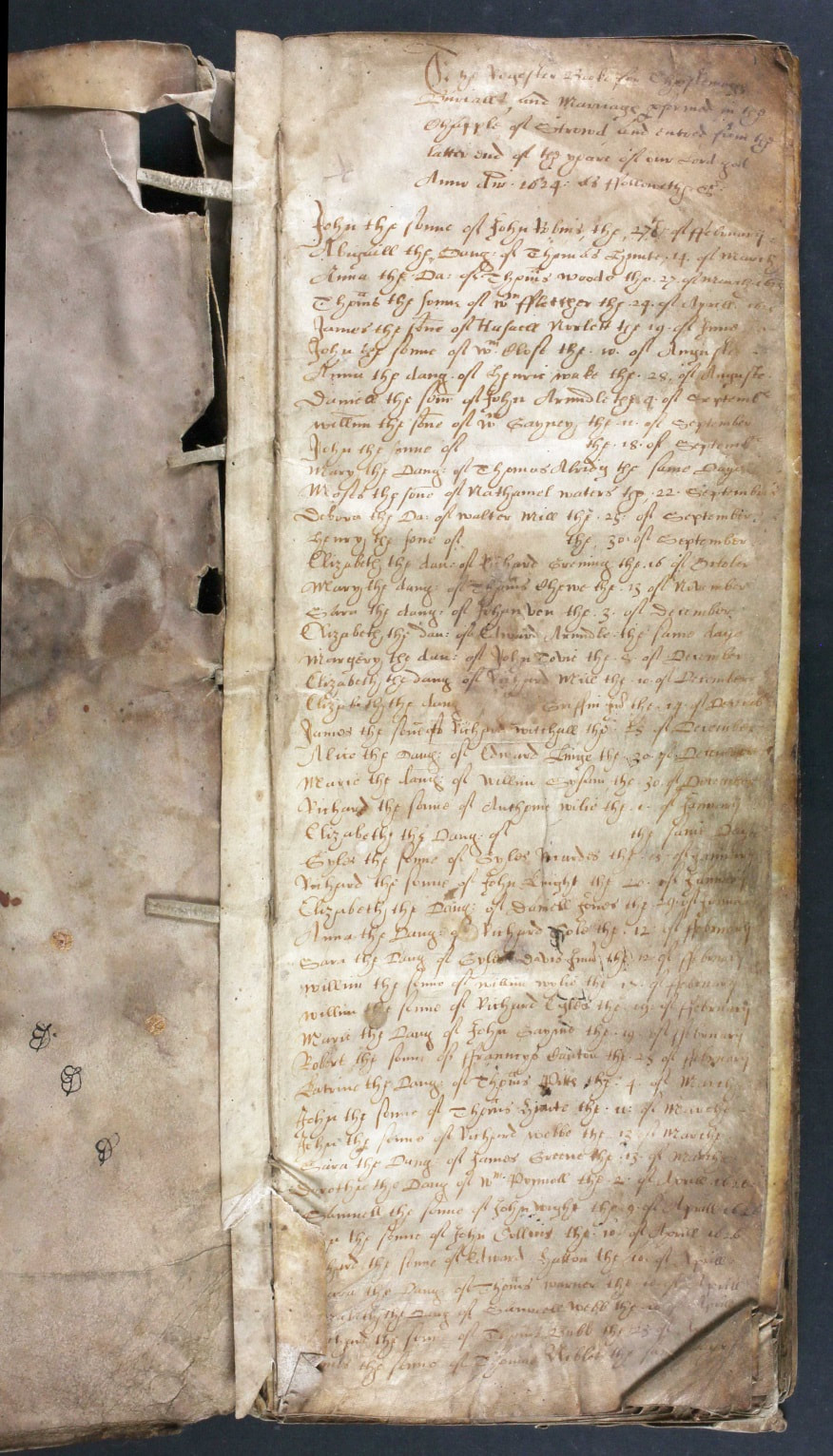

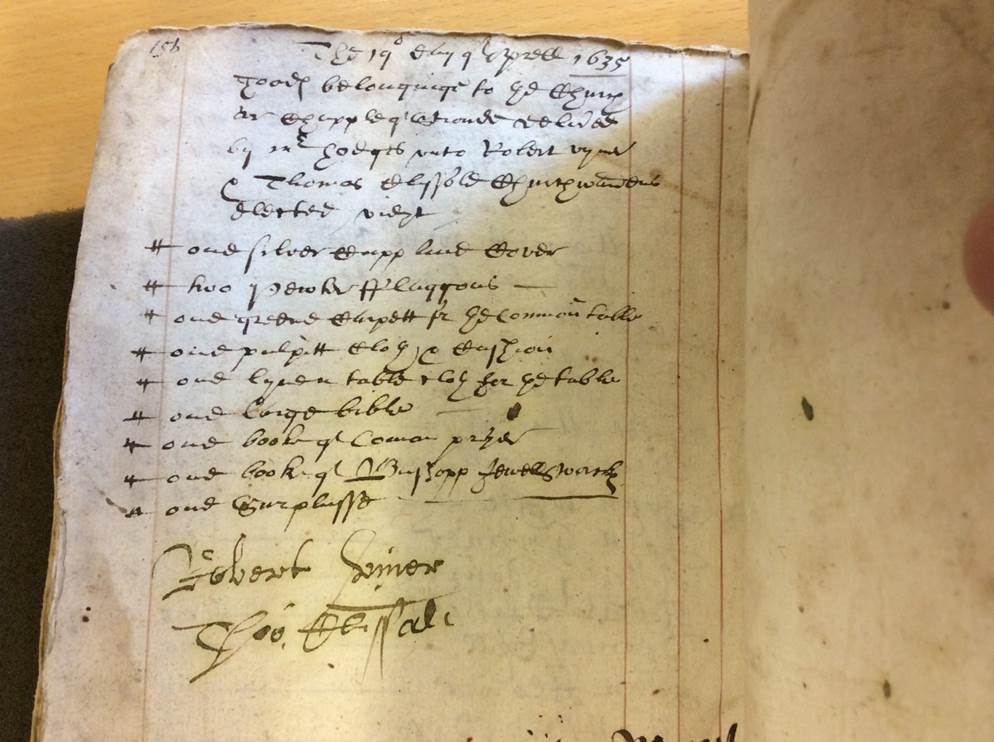

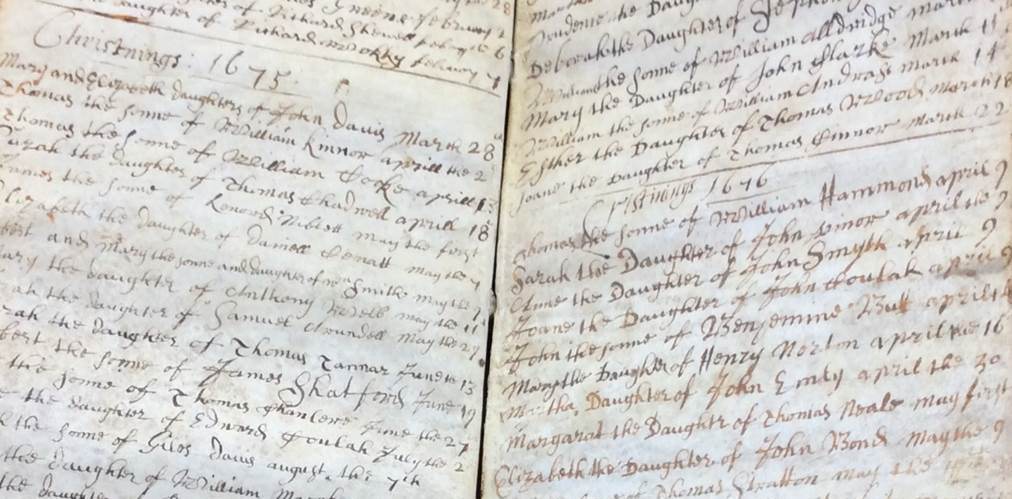

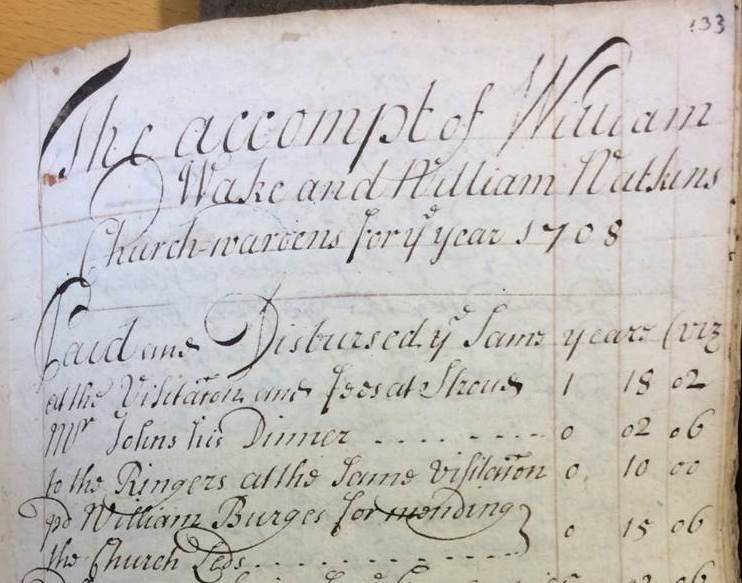

Parish registers in England were first instituted by Lord Cromwell in September 1538, while he was Vicar General to King Henry VIII. The oldest surviving parish records for St Laurence are Bishop’s Transcripts of the parish registers dating from 1578. A churchwarden’s account book dating from 1623 survives, and parish registers dating from 1624. Vestry papers survive from 1637, and overseers’ papers from 1658. All these are deposited, along with all subsequent church records and documents, with Gloucestershire Archives, and are accessible to the public by prior arrangement with them.

The 1500s were a time of much upheaval for the Church in England. In 1517, Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg, Germany, thus effectively starting the Reformation; and in England, Henry VIII’s dynastic ambitions had led to the break with the papacy in Rome in 1534. The earliest existing records of curates at Stroud during this period hint at the turmoil affecting the parish and its clergy. In March 1540, Anthony Parsons, a former friar and then curate at the church, was imprisoned in Gloucester Castle having been reported to Thomas Cromwell for 'ill preaching‘. He was sent to Windsor to be examined concerning heresy by the bishop of Salisbury, and was subsequently condemned to be burnt at the stake. John Foxe, in “Foxe’s Book of Martyrs” first published in 1563, records that upon being brought to the stake, Parsons asked for a drink which he drank to his fellow sufferers with the words, "Be merry, my brethren, and lift up your hearts to God; for after this sharp breakfast I trust we shall have a good dinner in the Kingdom of Christ, our Lord and Redeemer“.

Under Elizabeth I’s Act of Uniformity of 1559, only a new Book of Common Prayer was to be used in parish churches, and Catholic Mass became illegal. Meanwhile, the town of Stroud continued to grow during the period, and by 1563 the estimated population of the parish had risen to 130 households, and a trading area had begun to build up around the church in what is now known as The Shambles, The Cross, and High Street. Around 1590, John Throckmorton, the then Lord of Over (Upper) Lypiatt Manor, built a Market House here – now known as the Old Town Hall.

The Earliest Parish Records

Parish registers in England were first instituted by Lord Cromwell in September 1538, while he was Vicar General to King Henry VIII. The oldest surviving parish records for St Laurence are Bishop’s Transcripts of the parish registers dating from 1578. A churchwarden’s account book dating from 1623 survives, and parish registers dating from 1624. Vestry papers survive from 1637, and overseers’ papers from 1658. All these are deposited, along with all subsequent church records and documents, with Gloucestershire Archives, and are accessible to the public by prior arrangement with them.

The earliest surviving parish record: Bishop's Transcript, showing baptisms for April - August 1578

Churchwardens Account Book 1623-1716

The oldest surviving Parish Register, showing baptisms for August 1624 - May 1625

The development of Stroud owes much to the cloth industry, which can be traced back in the area to at least the 14th century. The surrounding Cotswold Hills had been used for sheep farming since ancient times, and a thriving wool trade had grown up. It was the growing industrialization of cloth manufacture in the mills which came to dominate the five valleys that converge on the town, that gave much of the impetus for Stroud’s growth, and by the early 1600s textile production was already the dominant industry. Two types of wool were produced: long fibre wool for worsted cloth, which was exported to the continent; and short fibre wool which was used for producing broadcloth. The valleys provided an abundant supply of water needed for processing the wool into cloth, and fulling mills were widespread. By the 1600s, most people were employed in the cloth trade. In 1608, there were 19 clothiers, 76 weavers, 33 fullers and 3 dyers recorded in the town.

Fighting Over the Pews

The allocation of pews has always had the potential to be a contentious issue. In 1609, a case between Jane Brewer and Alice Warner came before the Bishop’s Court in Gloucester, which heard cases which fell under ecclesiastical jurisdiction:

“On a Sunday before last Christmas Alice Warner, an aged woman, came to the church in Stroud to hear divine service and went into the seat where she usually sits. Jane Brewer and her husband Thomas came into the church and went to the seat where Alice Warner was and offered to go into the same seat but Alice held the door fast and would not suffer Jane to come in. Then Thomas Brewer came and by strength and force pulled open the door and both went into the seat. They were thrusting and shuffling against each other and in the end Alice Warren pulled the partlet from Jane's neck and threw it on the ground and pulled Thomas Brewer's band in such violent manner that she broke the loops from about his neck. Then she went out of the seat …. Webb [Richard Webb, broadweaver] saw all this because he was tolling one of the bells. He never saw Jane Brewer sit in the seat before but usually sat in another seat. There is room for 4 women in the seat.

On a Sunday Margaret Hobson saw Jane Brewer come from Stroud church a good while before morning prayer was ended. Jane sent for her mother, Joan Hobson, and Margaret Hobson, and told them that she was almost dead as Alice Warner had beaten her at church. She saw that Brewer's partlet was ripped off and her shins were black and blue in four places but she does not know if Warner had beaten her as she was not at morning service. Warner is an aged woman and midwife in the parish. She has sat in that seat a long time and part of it belongs to her dwelling house but Hobson has heard that part of it belongs to Brewer's house. She has never seen Jane Brewer sit there but in another seat in the church …. Elizabeth Brewer confirmed Hobson's account and added that since that Sunday she has heard Alice Warner say that Jane Brewer was a baggage and should not sit in the seat with her.”

The allocation of pews has always had the potential to be a contentious issue. In 1609, a case between Jane Brewer and Alice Warner came before the Bishop’s Court in Gloucester, which heard cases which fell under ecclesiastical jurisdiction:

“On a Sunday before last Christmas Alice Warner, an aged woman, came to the church in Stroud to hear divine service and went into the seat where she usually sits. Jane Brewer and her husband Thomas came into the church and went to the seat where Alice Warner was and offered to go into the same seat but Alice held the door fast and would not suffer Jane to come in. Then Thomas Brewer came and by strength and force pulled open the door and both went into the seat. They were thrusting and shuffling against each other and in the end Alice Warren pulled the partlet from Jane's neck and threw it on the ground and pulled Thomas Brewer's band in such violent manner that she broke the loops from about his neck. Then she went out of the seat …. Webb [Richard Webb, broadweaver] saw all this because he was tolling one of the bells. He never saw Jane Brewer sit in the seat before but usually sat in another seat. There is room for 4 women in the seat.

On a Sunday Margaret Hobson saw Jane Brewer come from Stroud church a good while before morning prayer was ended. Jane sent for her mother, Joan Hobson, and Margaret Hobson, and told them that she was almost dead as Alice Warner had beaten her at church. She saw that Brewer's partlet was ripped off and her shins were black and blue in four places but she does not know if Warner had beaten her as she was not at morning service. Warner is an aged woman and midwife in the parish. She has sat in that seat a long time and part of it belongs to her dwelling house but Hobson has heard that part of it belongs to Brewer's house. She has never seen Jane Brewer sit there but in another seat in the church …. Elizabeth Brewer confirmed Hobson's account and added that since that Sunday she has heard Alice Warner say that Jane Brewer was a baggage and should not sit in the seat with her.”

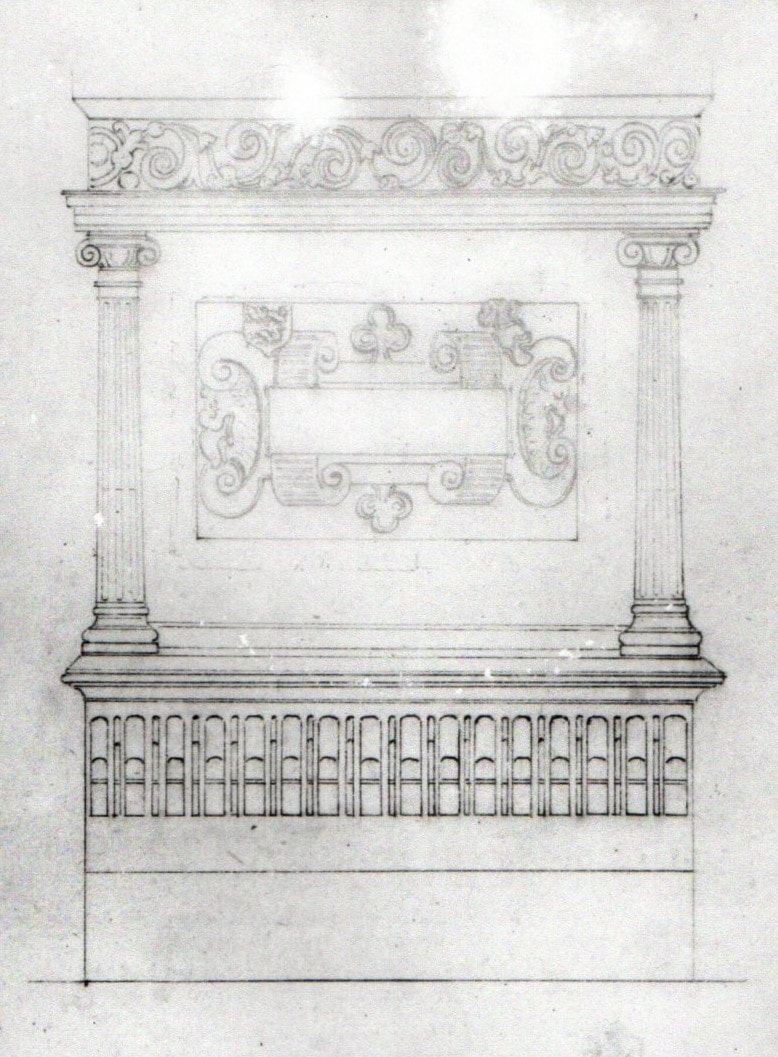

The Thomas Stephens Memorial

The development of Stroud owes much to the woollen cloth industry, which can be traced back in the area to at least the 14th century. It was the growing industrialization of cloth manufacture in the mills which came to dominate the five valleys that converge on the town, that gave much of the impetus for Stroud’s growth, and by the early 1600s textile production was the dominant industry. The most striking monument in the church today is that of Thomas Stephens of Lypiatt, now in the east wall of the south transept, and dating to 1613. The son of Edward Stephens of Eastington, Thomas was a Middle Temple lawyer, who obtained a court appointment under King James I (whose ‘King James Bible’ was published in 1611). He was Attorney General to both Henry and Charles Stuart; Charles later becoming King Charles I.

The development of Stroud owes much to the woollen cloth industry, which can be traced back in the area to at least the 14th century. It was the growing industrialization of cloth manufacture in the mills which came to dominate the five valleys that converge on the town, that gave much of the impetus for Stroud’s growth, and by the early 1600s textile production was the dominant industry. The most striking monument in the church today is that of Thomas Stephens of Lypiatt, now in the east wall of the south transept, and dating to 1613. The son of Edward Stephens of Eastington, Thomas was a Middle Temple lawyer, who obtained a court appointment under King James I (whose ‘King James Bible’ was published in 1611). He was Attorney General to both Henry and Charles Stuart; Charles later becoming King Charles I.

Stephens made a fortunate marriage in Elizabeth, daughter of John Stone of London, and a few years before his death purchased the Gloucestershire manors of Cherington, Over (Upper) Lypiatt, and Chipping, Little and Old Sodbury. He died on 26 April 1613. The effigy shows him kneeling at a prayer desk and in his lawyers’ robes, and it was probably sculpted by Samuel Baldwin of Stroud. The Latin inscription was translated by Paul Hawkins Fisher in the 19th century as:

“Died Stephens by the law? The law alas! kills all,

That law which doom'd our sinful race to die.

But Stephens lives: another law, Christ's law withal,

Gives him a crown and immortality.”

That law which doom'd our sinful race to die.

But Stephens lives: another law, Christ's law withal,

Gives him a crown and immortality.”

The Stephens family were Lords of Over Lypiatt Manor for five generations, and to the right of Thomas’ memorial is a stone to the last of the Lypiatt branch, John Stephens, “A gentleman universally esteemed for his integrity and benevolent disposition”, who died in 1778. The Stephens family vault lies beneath the floor in this part of the church. It was uncovered by workmen in 1833, and again in 1868.

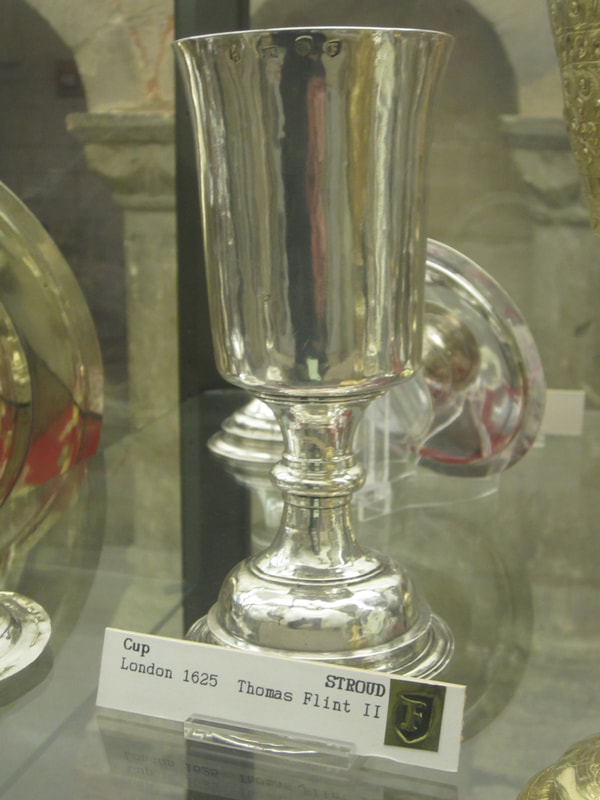

Church Treasure

The churchwarden’s account book records that in 1625, £2 18s was “payde for the exchaing [exchanging] of the comunion cup”. Hallmarked for Thomas Flint II of London, the chalice is now on permanent display in Gloucester Cathedral Treasury. Other church treasures on display in the Cathedral Treasury are a chalice purchased in 1670 for the sum of £5 7s 6d, hallmarked for Daniel Rutty of London; a Church Plate, hallmarked for Rebecca Emes and Edward Barnard of London in 1814, and inscribed with the names of the churchwardens William Chambers and Richard Cooke; and a Communion Set formerly belonging to Stroud-born Revd Arthur Henry Stanton, hallmarked for Jes Berkentin of London in 1873.

The churchwarden’s account book records that in 1625, £2 18s was “payde for the exchaing [exchanging] of the comunion cup”. Hallmarked for Thomas Flint II of London, the chalice is now on permanent display in Gloucester Cathedral Treasury. Other church treasures on display in the Cathedral Treasury are a chalice purchased in 1670 for the sum of £5 7s 6d, hallmarked for Daniel Rutty of London; a Church Plate, hallmarked for Rebecca Emes and Edward Barnard of London in 1814, and inscribed with the names of the churchwardens William Chambers and Richard Cooke; and a Communion Set formerly belonging to Stroud-born Revd Arthur Henry Stanton, hallmarked for Jes Berkentin of London in 1873.

Church silver on display in Gloucester Cathedral Treasury

A Rare Survivor?

It has been suggested by Lionel Walrond and Stroud Local History Society that the church has a rare surviving example of what is known as a ‘dole table’, dating to the 16th or 17th century. Whilst no documentary evidence has been found to support this, there is a stone at the south end of the external west wall which could be a candidate. The stone is much damaged and eroded, and has been repaired with three large steel staples. It is also possible that the stone is currently laid upside down. As to the use of the stone, this is also subject to debate. Dole tables were usually used for the distribution of food (notably bread) and drink to the poor. Alternatively, it has been suggested that this stone may have been used by the poor to place a shrouded body on for burial, when a full traditional funeral could not be afforded. Indents in the four corners may have been to hold candles for a reverential display.

It has been suggested by Lionel Walrond and Stroud Local History Society that the church has a rare surviving example of what is known as a ‘dole table’, dating to the 16th or 17th century. Whilst no documentary evidence has been found to support this, there is a stone at the south end of the external west wall which could be a candidate. The stone is much damaged and eroded, and has been repaired with three large steel staples. It is also possible that the stone is currently laid upside down. As to the use of the stone, this is also subject to debate. Dole tables were usually used for the distribution of food (notably bread) and drink to the poor. Alternatively, it has been suggested that this stone may have been used by the poor to place a shrouded body on for burial, when a full traditional funeral could not be afforded. Indents in the four corners may have been to hold candles for a reverential display.

A rare surviving example of a dole table?

The Bells

The church is known to have had six bells by 1629, when five of them were recast by Roger Purdue. In about 1775 the tower contained eight bells; two of the eight had been cast by Abraham Rudhall in 1713 and 1721 respectively, and two by Thomas Rudhall in 1771. In 1814, whilst the ringers were ringing a peal, the tenor bell fell from its supports and cracked one of the other bells. Fortunately, no one was injured. The two of the bells were recast the following year by Thomas Mears of Whitechapel, and two more were added to the peal to make the current total of ten. The bells were overhauled and re-framed in cast iron by Loughborough Bellfoundry in 1893. A further renovation of the bells was supported by Stroud Preservation Trust in 1989. Records show that 173 full peals of the bells have been rung since 1772, the latest being in August 2015. The bell tower also houses a clock constructed by Smiths Steamclock Company of Clerkenwell, London. It has three six-foot diameter dials, with Westminster chimes every 15 minutes and hourly striking. It was converted to electric operation in 1973, but was restored to its original state, except for electric winding, in 1989. Adjacent to the clock is a large carillon, said to be the best example in Gloucestershire. This instrument can play seven hymns and also includes a set of chimes, working in conjunction with the bells.

The church is known to have had six bells by 1629, when five of them were recast by Roger Purdue. In about 1775 the tower contained eight bells; two of the eight had been cast by Abraham Rudhall in 1713 and 1721 respectively, and two by Thomas Rudhall in 1771. In 1814, whilst the ringers were ringing a peal, the tenor bell fell from its supports and cracked one of the other bells. Fortunately, no one was injured. The two of the bells were recast the following year by Thomas Mears of Whitechapel, and two more were added to the peal to make the current total of ten. The bells were overhauled and re-framed in cast iron by Loughborough Bellfoundry in 1893. A further renovation of the bells was supported by Stroud Preservation Trust in 1989. Records show that 173 full peals of the bells have been rung since 1772, the latest being in August 2015. The bell tower also houses a clock constructed by Smiths Steamclock Company of Clerkenwell, London. It has three six-foot diameter dials, with Westminster chimes every 15 minutes and hourly striking. It was converted to electric operation in 1973, but was restored to its original state, except for electric winding, in 1989. Adjacent to the clock is a large carillon, said to be the best example in Gloucestershire. This instrument can play seven hymns and also includes a set of chimes, working in conjunction with the bells.

Samuel Watts' Bequest

In 1631, Samuel Watts, a London merchant and native of Stroud, bequeathed £200: half for a lectureship at the church, and half for relief of the poor. The money was later used to buy land at Colethrop which was vested in the name of the Stroud Feoffees. The feoffees were a charitable trust dating back to the deed of composition in 1304, when the parishioners at Stroud were assigned land formerly rented to John de Pridie (‘Pridie’s Acre’ – now The Shambles), which was to be used to fund church maintenance and pay the chaplain’s stipend. By the mid 17th century, the feoffees had various properties on this land, as well as near The Cross, and on the south side of the High Street, and they were also using their income for the relief of the poor, and to fund apprenticeships for local boys. The trust still exists today, now relying solely on income generated from investments. This is distributed between St Laurence and Holy Trinity churches, and an educational charity.

In 1631, Samuel Watts, a London merchant and native of Stroud, bequeathed £200: half for a lectureship at the church, and half for relief of the poor. The money was later used to buy land at Colethrop which was vested in the name of the Stroud Feoffees. The feoffees were a charitable trust dating back to the deed of composition in 1304, when the parishioners at Stroud were assigned land formerly rented to John de Pridie (‘Pridie’s Acre’ – now The Shambles), which was to be used to fund church maintenance and pay the chaplain’s stipend. By the mid 17th century, the feoffees had various properties on this land, as well as near The Cross, and on the south side of the High Street, and they were also using their income for the relief of the poor, and to fund apprenticeships for local boys. The trust still exists today, now relying solely on income generated from investments. This is distributed between St Laurence and Holy Trinity churches, and an educational charity.

By 1650, the population of Stroud had risen quite considerably, and was estimated to consist of around 600 families. However, the country as a whole was going through another period of turmoil. The English Civil war broke out between the Royalists and Parliamentarians in 1642, which was to lead to the execution of Charles I in 1649, followed by the establishment of Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth, before the monarchy was finally restored under Charles II in 1660. An entry in the churchwarden’s account book around this time records that £1 10s had to be paid out for “Leading & glassing the church wyndoes being broken by the soldiers and prisonners” – presumably, the prisoners were being held captive in the church.

The Fight for the Right to Appoint to the Curacy

When the curacy of the church became vacant in 1721, a long-standing argument broke out once again as to whether the parishioners or the Bishop of Gloucester had the power of appointment to it. Henry Bond was appointed by the bishop in spite of the rival claims of a Mr Bedford, who was said to be supported by a majority of the parishioners and local landowners. The dispute and ill-feeling rumbled on for many years, and it wasn’t until 1741 that the Lord Chancellor finally found in favour of Bond, and the church effectively became what is known as a ‘perpetual curacy’ subject to the nomination of the bishop. In spite of the controversy surrounding his appointment, the relationship between Bond and his parishioners became friendlier over time, and he was praised for his work in the parish, particularly for his interest in the conduct and improvement of the charity schools. Bond will also have been aware of a visit to Stroud by the preacher John Wesley in June 1742, when he preached a sermon in the nearby Shambles, where a plaque today commemorates how he made use of a butcher’s block to stand on as he preached.

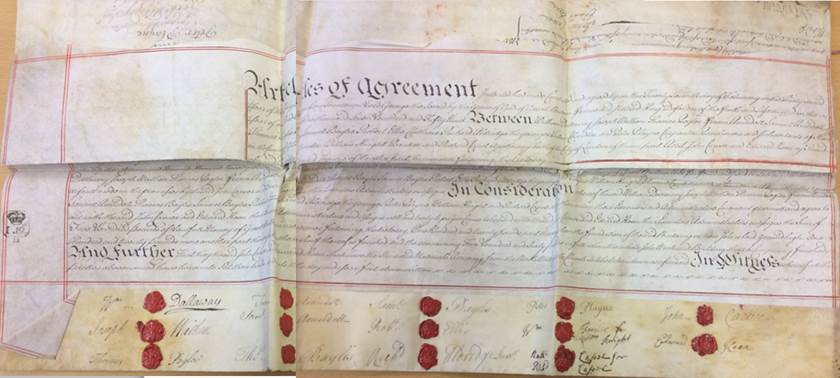

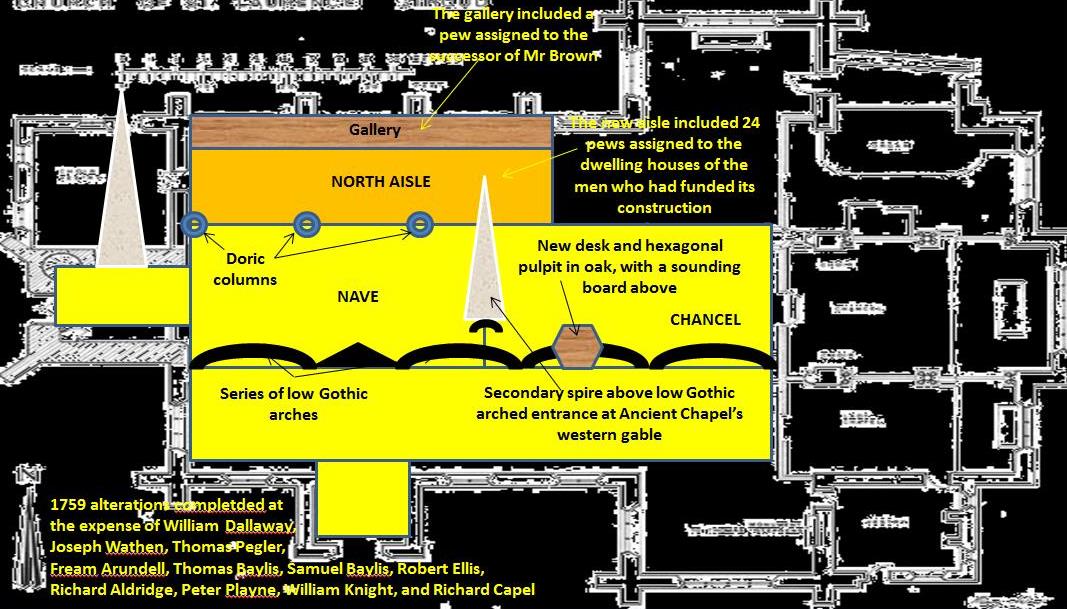

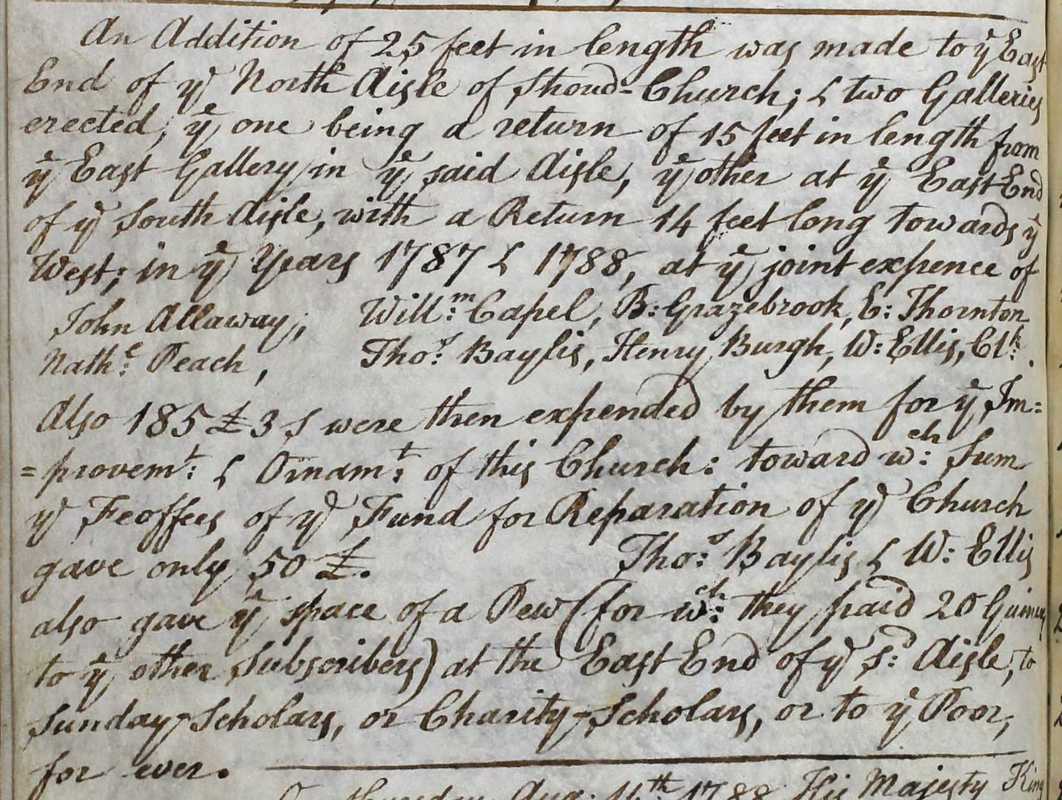

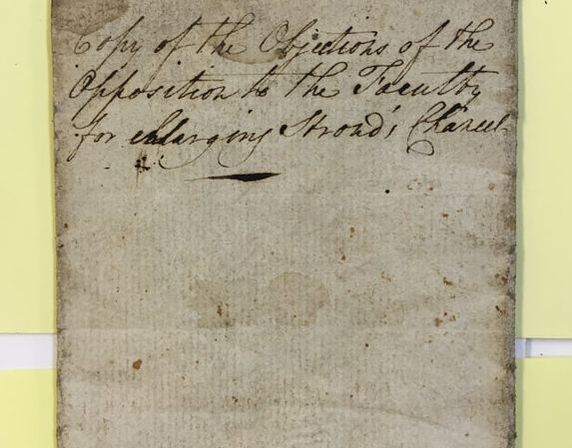

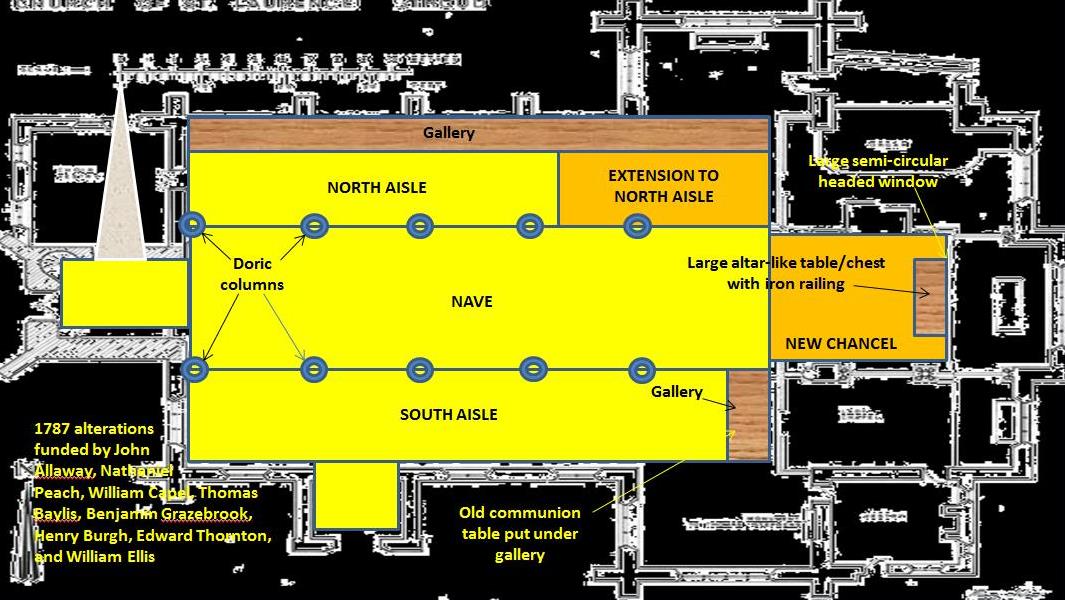

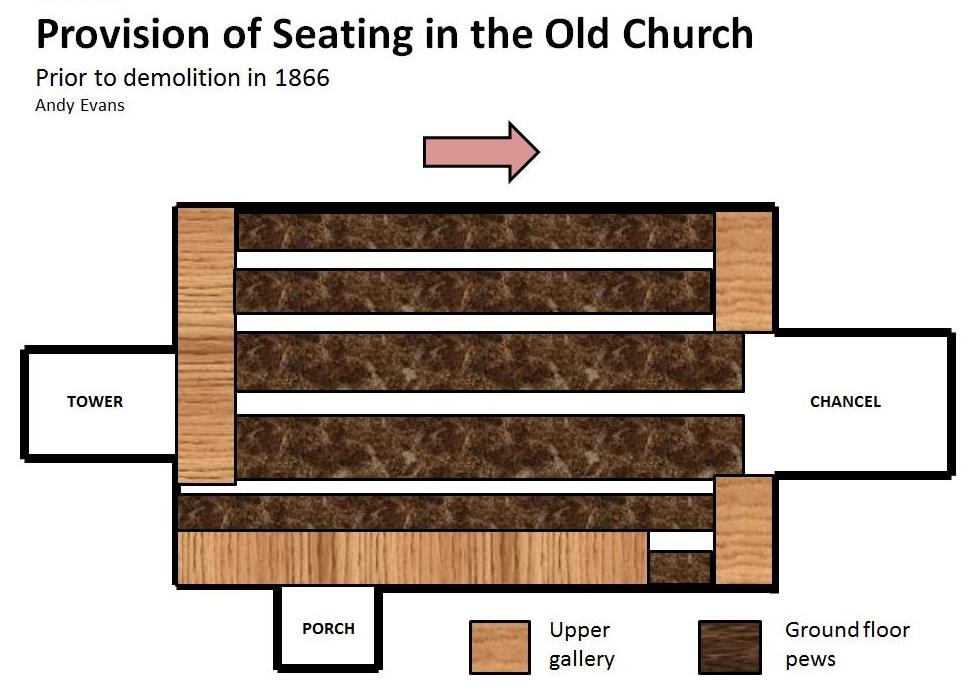

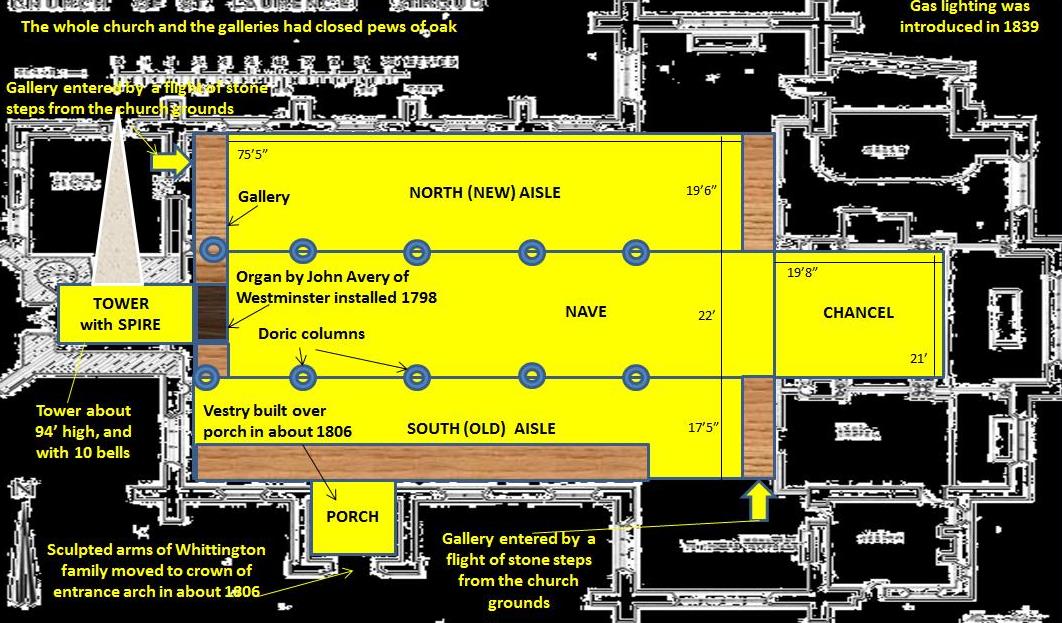

The North Aisle

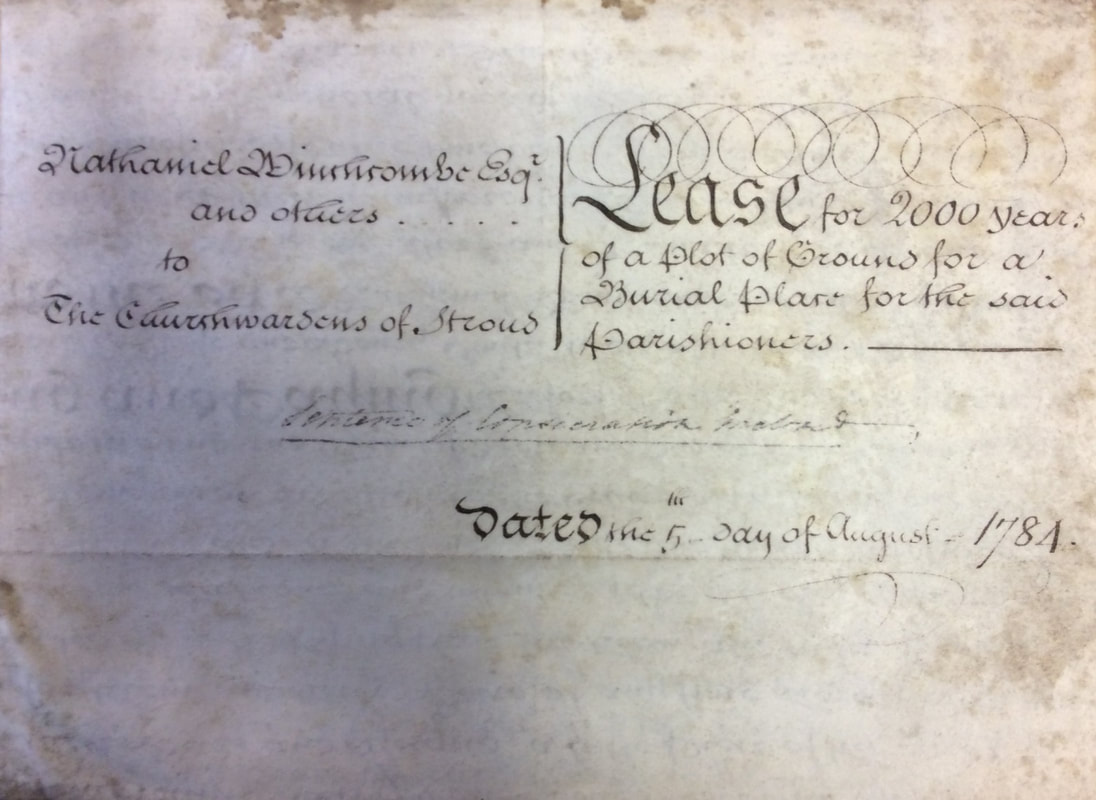

It wasn’t until the 18th century that the parishioners finally got around to adding a north aisle. The first part, running the length of the nave, was added in 1759; with the second and final part, including an extension to the chancel, being added between 1787 and 1795. The church also purchased some additional land on its northern side in 1784, to become a new burial ground.

When the curacy of the church became vacant in 1721, a long-standing argument broke out once again as to whether the parishioners or the Bishop of Gloucester had the power of appointment to it. Henry Bond was appointed by the bishop in spite of the rival claims of a Mr Bedford, who was said to be supported by a majority of the parishioners and local landowners. The dispute and ill-feeling rumbled on for many years, and it wasn’t until 1741 that the Lord Chancellor finally found in favour of Bond, and the church effectively became what is known as a ‘perpetual curacy’ subject to the nomination of the bishop. In spite of the controversy surrounding his appointment, the relationship between Bond and his parishioners became friendlier over time, and he was praised for his work in the parish, particularly for his interest in the conduct and improvement of the charity schools. Bond will also have been aware of a visit to Stroud by the preacher John Wesley in June 1742, when he preached a sermon in the nearby Shambles, where a plaque today commemorates how he made use of a butcher’s block to stand on as he preached.

The North Aisle

It wasn’t until the 18th century that the parishioners finally got around to adding a north aisle. The first part, running the length of the nave, was added in 1759; with the second and final part, including an extension to the chancel, being added between 1787 and 1795. The church also purchased some additional land on its northern side in 1784, to become a new burial ground.

Plan of the church by 1759

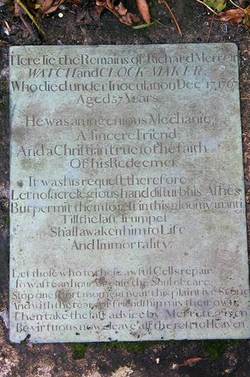

Under Inoculation

In the church grounds is a plaque to Richard Merrett, a local watch and clock maker, who died in 1767 “under inoculation”. Merrett's death occurred before GP Edward Jenner, of nearby Berkeley, embarked on a series of experiments in the 1790s to find a cure for smallpox. It is possible that the inoculation referred to in this inscription was "variolation“, which was another, and often successful, means of combating smallpox. It was a procedure introduced into England in 1721 from the East by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the British Ambassador in Turkey.

In the church grounds is a plaque to Richard Merrett, a local watch and clock maker, who died in 1767 “under inoculation”. Merrett's death occurred before GP Edward Jenner, of nearby Berkeley, embarked on a series of experiments in the 1790s to find a cure for smallpox. It is possible that the inoculation referred to in this inscription was "variolation“, which was another, and often successful, means of combating smallpox. It was a procedure introduced into England in 1721 from the East by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the British Ambassador in Turkey.

Here lie the Remains of Richard Merrett

WATCH and CLOCK MAKER

Who died under Inoculation on Dec. 17. 1767

Aged 57 Years

He was an ingenious Mechanic,

A sincere Friend;

And a Christian true to the faith

Of his Redeemer.

It was his request therefore

Let no sacrelegious hand disturb his Ashes

But permit them to rest in this gloomy mantion

Till the last Trumpet

Shall awaken him to Life

And Immortality.

Let those who to these awful Cells repair,

To waste an hour or ease the Soul of care,

Stop one short moment near this plaintive Stone

And with the tears of friendship mix their own;

Then take the last advice by Merrett given,

Be virtuous now - leave all the rest to Heaven

WATCH and CLOCK MAKER

Who died under Inoculation on Dec. 17. 1767

Aged 57 Years

He was an ingenious Mechanic,

A sincere Friend;

And a Christian true to the faith

Of his Redeemer.

It was his request therefore

Let no sacrelegious hand disturb his Ashes

But permit them to rest in this gloomy mantion

Till the last Trumpet

Shall awaken him to Life

And Immortality.

Let those who to these awful Cells repair,

To waste an hour or ease the Soul of care,

Stop one short moment near this plaintive Stone

And with the tears of friendship mix their own;

Then take the last advice by Merrett given,

Be virtuous now - leave all the rest to Heaven

Re-Pewing the Church

In 1769 the church was re-pewed. In all, 454 seats were added in 52 pews (the typical pew sat 10 people); and the cost of each seat (paid for by subscribers) was 11s 6d (about £70 in today’s money – about £700 per pew). The biggest contributors were John Stephens Esq (29 seats), Thomas Gryffin Esq (26 seats), and Peter Leversage (18 seats). The details of the re-pewing were recorded by Rev John Williams in the parish register after the 1812 burial entries, using an original list from a book belonging to Rev John Colborne, Parish Feoffee.

In 1769 the church was re-pewed. In all, 454 seats were added in 52 pews (the typical pew sat 10 people); and the cost of each seat (paid for by subscribers) was 11s 6d (about £70 in today’s money – about £700 per pew). The biggest contributors were John Stephens Esq (29 seats), Thomas Gryffin Esq (26 seats), and Peter Leversage (18 seats). The details of the re-pewing were recorded by Rev John Williams in the parish register after the 1812 burial entries, using an original list from a book belonging to Rev John Colborne, Parish Feoffee.

The Opening of the Navigable Canal from Framilode to Walbridge

The opening of the navigable canal from Framilode to Walbridge in 1779 was recorded in the Parish Register:

“On Wednesday, July the 21st, 1779, the navigable Canal from Framilode to Walbridge was opened. Sir George Onesiphorus Paul, the Chairman, Sir Willm Guise, and Willm Bromley Chester, Esq., Members of Parliament for the County, and many principal Gentlemen and Tradesmen went in procession with the company of proprietors, preceded by a Band of Music, Flags and Banners, from a large Booth erected in the area before the Market House, and covered with Cloth, through the Town to the Quay at Walbridge; where, taking boats, they passed through the two first locks to Ebley Mill; whence they returned with three large vessels freighted with coals, wooll, salt, and other goods to the Quay (where an Ox was roasted for the populace), and afterwards dined in the Booth with great Festivity and Harmony.”

The opening of the navigable canal from Framilode to Walbridge in 1779 was recorded in the Parish Register:

“On Wednesday, July the 21st, 1779, the navigable Canal from Framilode to Walbridge was opened. Sir George Onesiphorus Paul, the Chairman, Sir Willm Guise, and Willm Bromley Chester, Esq., Members of Parliament for the County, and many principal Gentlemen and Tradesmen went in procession with the company of proprietors, preceded by a Band of Music, Flags and Banners, from a large Booth erected in the area before the Market House, and covered with Cloth, through the Town to the Quay at Walbridge; where, taking boats, they passed through the two first locks to Ebley Mill; whence they returned with three large vessels freighted with coals, wooll, salt, and other goods to the Quay (where an Ox was roasted for the populace), and afterwards dined in the Booth with great Festivity and Harmony.”

Lease (for 2,000 years!) for a Plot of Ground for a Burial Place, 5 August 1784 - being the provision of a burial ground to the north of the church

LEFT: Note in the Parish Register regarding the further extension of the North Aisle, 1788

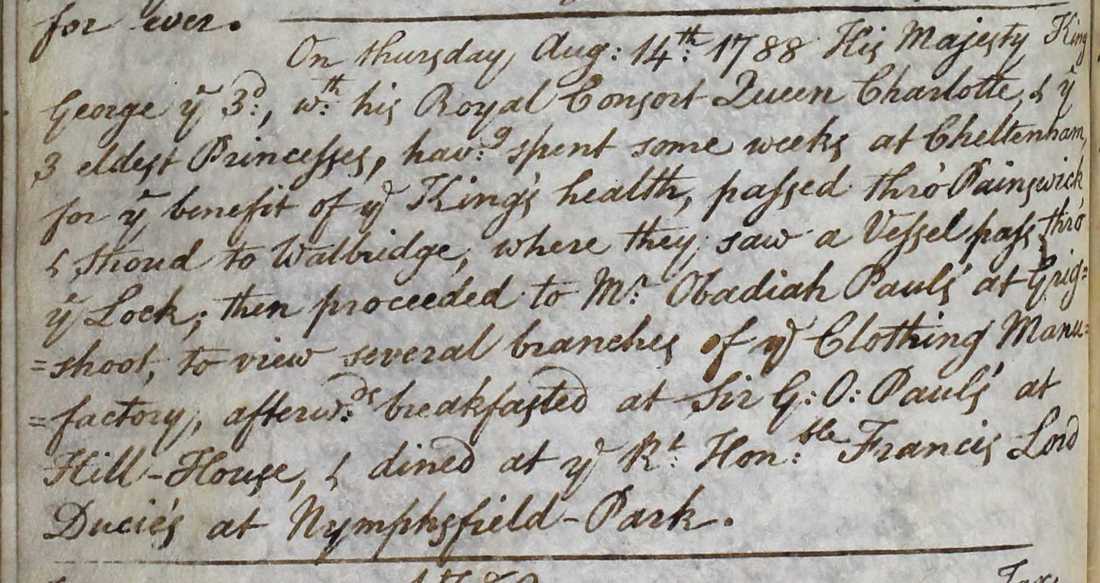

RIGHT: Note in the Parish Register regarding the visit of King George III to Walbridge, 14 August 1788

RIGHT: Note in the Parish Register regarding the visit of King George III to Walbridge, 14 August 1788

Plan of the church after the addition of the second portion of the North Aisle and the New Chancel from 1787 to 1795

A note in the church registers after the 1802 baptisms, gives an insight into the population of the parish at that time:

"By an accurate enumeration made in April 1801 the population of the parish appears to be as follows: Males 2602, females 2820, total 5422. (The greater number of females is owing to a destructive war, of which this was the 8th year ). Families 1355; inhabited houses 1033, uninhabited 15. Traders or manufacturers 3711; Agriculturers 240; Independents, aged and infants 1465. About 1200 more than Bisley, and about 1600 more than Painswick. In the year 1784 by a calculation, the number of inhabitants was supposed to be 4,542. The subsequent increase was occasioned by the introduction of cloth making".

The ‘destructive war’ referred to was that which broke out in 1793 in the wake of the French Revolution, and which was to end in 1815 with the Duke of Wellington’s defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo.

"By an accurate enumeration made in April 1801 the population of the parish appears to be as follows: Males 2602, females 2820, total 5422. (The greater number of females is owing to a destructive war, of which this was the 8th year ). Families 1355; inhabited houses 1033, uninhabited 15. Traders or manufacturers 3711; Agriculturers 240; Independents, aged and infants 1465. About 1200 more than Bisley, and about 1600 more than Painswick. In the year 1784 by a calculation, the number of inhabitants was supposed to be 4,542. The subsequent increase was occasioned by the introduction of cloth making".

The ‘destructive war’ referred to was that which broke out in 1793 in the wake of the French Revolution, and which was to end in 1815 with the Duke of Wellington’s defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo.

John Hollings' Tomb

In the south church grounds is the tomb of John Hollings, resembling a stepped pyramid. A retired mercer, banker and JP, Hollings was appointed Captain of the Loyal Volunteers in 1798, when they were formed as part of the nation’s response to the threat of invasion by Napoleon. However, Hollings was not universally popular, and is said to have had an argument with an adversary, who declared he would like to live long enough to see him “safe underground”. Hollings replied “That you never shall!” As a precaution Hollings decreed that when his time came – which it did in 1805 – his coffin should not be interred but should be left on the surface and covered with the monument that we see today.

In the south church grounds is the tomb of John Hollings, resembling a stepped pyramid. A retired mercer, banker and JP, Hollings was appointed Captain of the Loyal Volunteers in 1798, when they were formed as part of the nation’s response to the threat of invasion by Napoleon. However, Hollings was not universally popular, and is said to have had an argument with an adversary, who declared he would like to live long enough to see him “safe underground”. Hollings replied “That you never shall!” As a precaution Hollings decreed that when his time came – which it did in 1805 – his coffin should not be interred but should be left on the surface and covered with the monument that we see today.

The Delmont Duel

Probably the best known grave in the church grounds is that of Lieutenant Joseph Francis Delmont of the 82nd Regiment, who died on the 18th August 1807 of wounds received in a duel, which took place in the grounds of The Grange in Folly Lane. Delmont had made a remark to Lieutenant Benjamin Heazle that caused offence, and which he refused to apologise for. It was decided to settle the matter by a duel. Finding a couple of pistols in Stroud at short notice proved difficult, and Delmont ended up with a rusty one. Delmont was still preparing to shoot when Heazle fired his pistol, seriously wounding Delmont. The drama was compounded when the nurse tending him with a lotion for bathing his wounds, gave it to him to drink instead. He lasted a few days, being ministered to by Rev John Williams, before finally passing away. The following Sunday Williams preached a sermon at the church on “the pernicious vice of duelling”, which was later published. Delmont’s grave is in the far southwest corner of the church grounds.

Probably the best known grave in the church grounds is that of Lieutenant Joseph Francis Delmont of the 82nd Regiment, who died on the 18th August 1807 of wounds received in a duel, which took place in the grounds of The Grange in Folly Lane. Delmont had made a remark to Lieutenant Benjamin Heazle that caused offence, and which he refused to apologise for. It was decided to settle the matter by a duel. Finding a couple of pistols in Stroud at short notice proved difficult, and Delmont ended up with a rusty one. Delmont was still preparing to shoot when Heazle fired his pistol, seriously wounding Delmont. The drama was compounded when the nurse tending him with a lotion for bathing his wounds, gave it to him to drink instead. He lasted a few days, being ministered to by Rev John Williams, before finally passing away. The following Sunday Williams preached a sermon at the church on “the pernicious vice of duelling”, which was later published. Delmont’s grave is in the far southwest corner of the church grounds.

Edmund Kean's Marriage

Edmund Kean (1787-1833) was a celebrated Shakesperean stage actor, well known for his short stature, tumultuous personal life, and controversial divorce. He died of his excesses at the age of 44. In 1808, Kean joined Samuel Butler’s provincial troupe and on 17th July of that year he married the leading actress Mary Chambers of Waterford, Ireland, at St Laurence Church. At that time, Mary had been lodging at Thornton’s in Church Street, Stroud. Unfortunately, Kean's lifestyle became a considerable hindrance to his career and personal life. As a result of his relationship with Charlotte Cox, the wife of a London city alderman, he was sued by Mr Cox in 1825 for damages for ‘criminal conversation’ (adultery). The jury deliberated for just ten minutes, and damages of £800 were awarded against Kean. Subsequently, The Times newspaper launched a violent attack on him. Needless to say, the case caused his wife Mary to leave him, and aroused such bitter feelings against him from the public that he was booed and pelted with fruit when he re-appeared at Drury Lane. His last appearance on stage was at Covent Garden in 1833, when he played Othello, dying later that year at Richmond in Surrey. His last words were alleged to have been, "dying is easy; comedy is hard.“ His wife Mary bore him two sons, one of whom was the actor Charles Kean.

Edmund Kean (1787-1833) was a celebrated Shakesperean stage actor, well known for his short stature, tumultuous personal life, and controversial divorce. He died of his excesses at the age of 44. In 1808, Kean joined Samuel Butler’s provincial troupe and on 17th July of that year he married the leading actress Mary Chambers of Waterford, Ireland, at St Laurence Church. At that time, Mary had been lodging at Thornton’s in Church Street, Stroud. Unfortunately, Kean's lifestyle became a considerable hindrance to his career and personal life. As a result of his relationship with Charlotte Cox, the wife of a London city alderman, he was sued by Mr Cox in 1825 for damages for ‘criminal conversation’ (adultery). The jury deliberated for just ten minutes, and damages of £800 were awarded against Kean. Subsequently, The Times newspaper launched a violent attack on him. Needless to say, the case caused his wife Mary to leave him, and aroused such bitter feelings against him from the public that he was booed and pelted with fruit when he re-appeared at Drury Lane. His last appearance on stage was at Covent Garden in 1833, when he played Othello, dying later that year at Richmond in Surrey. His last words were alleged to have been, "dying is easy; comedy is hard.“ His wife Mary bore him two sons, one of whom was the actor Charles Kean.

Mrs Sarah Sweeting

Mrs Sarah Sweeting A plot of land was purchased for a new burial ground on the north side of the church From Mrs Sarah Sweeting in August 1810. Sarah was subsequently buried at St Laurence on 6 January 1825, aged 83. She was baptised at St Laurence in 1741, the daughter of Michael Ballard, and had married David Sweeting at St Laurence in 1763. Her address at death was given as Ryeford, Stonehouse, and she was a widow. Probate for her Will was given 7 April 1825. Her beneficiaries were: £100 to her son Daniel Niblett Sweeting (a painter, plumber and glazier in Tetbury); £100 to John Tyler Jones, a chemist and druggist of Stroud (married to her grand-daughter Mary Sarah Sweeting); £50 to Spencer Lambert, a coffee roaster of Aldgate, London (related to Sarah through his wife, Mary Ann Ballard); “My pew or seat in the Parish Church of Stroud” to her son Charles Page Sweeting; “Five guineas each to purchase a mourning ring to wear in remembrance of me” to her friends Charles Newman, a gentleman of Stroud, and Mary Hill, a spinster of Ryeford; “My gold watch with its appendages” to her grand-daughter Sarah Bishop; The remainder of the estate to her grand-daughter and executrix Martha Beata Miles. Sarah’s son Charles Page Sweeting was a surgeon living in King Street, Stroud. He was the surgeon who attended the fatally wounded Lt Delmont in 1807. He was also a founding trustee of Stroud Subscription Rooms. On 22 December 1829, John Purcell, a cabinet maker of Stroud, was fined £5 after pleading guilty to unlawfully selling a hare to Charles Sweeting for 2s 6d. They had been informed on by Henry Rudge.

Mrs Sarah Sweeting A plot of land was purchased for a new burial ground on the north side of the church From Mrs Sarah Sweeting in August 1810. Sarah was subsequently buried at St Laurence on 6 January 1825, aged 83. She was baptised at St Laurence in 1741, the daughter of Michael Ballard, and had married David Sweeting at St Laurence in 1763. Her address at death was given as Ryeford, Stonehouse, and she was a widow. Probate for her Will was given 7 April 1825. Her beneficiaries were: £100 to her son Daniel Niblett Sweeting (a painter, plumber and glazier in Tetbury); £100 to John Tyler Jones, a chemist and druggist of Stroud (married to her grand-daughter Mary Sarah Sweeting); £50 to Spencer Lambert, a coffee roaster of Aldgate, London (related to Sarah through his wife, Mary Ann Ballard); “My pew or seat in the Parish Church of Stroud” to her son Charles Page Sweeting; “Five guineas each to purchase a mourning ring to wear in remembrance of me” to her friends Charles Newman, a gentleman of Stroud, and Mary Hill, a spinster of Ryeford; “My gold watch with its appendages” to her grand-daughter Sarah Bishop; The remainder of the estate to her grand-daughter and executrix Martha Beata Miles. Sarah’s son Charles Page Sweeting was a surgeon living in King Street, Stroud. He was the surgeon who attended the fatally wounded Lt Delmont in 1807. He was also a founding trustee of Stroud Subscription Rooms. On 22 December 1829, John Purcell, a cabinet maker of Stroud, was fined £5 after pleading guilty to unlawfully selling a hare to Charles Sweeting for 2s 6d. They had been informed on by Henry Rudge.

Thomas Hughes, Surgeon

Thomas Hughes was born in Dursley in 1742. He was an apothecary and surgeon who moved to Stroud High Street in 1771, and who kept detailed weather records up to the year of his death in 1813. He was buried at St Laurence. His weather diaries, which were eventually given to the Royal Meteorological Society, provide a major contribution to what is known about the climate of the late 18th century.

Thomas Hughes was born in Dursley in 1742. He was an apothecary and surgeon who moved to Stroud High Street in 1771, and who kept detailed weather records up to the year of his death in 1813. He was buried at St Laurence. His weather diaries, which were eventually given to the Royal Meteorological Society, provide a major contribution to what is known about the climate of the late 18th century.

James Ferrabee, Engineer

James Ferrabee, son of John Ferrabee (an engineer from Thrupp) and his wife Esther, was baptised at St Laurence on 13th December 1818. He established the Phoenix Iron Works foundry at Thrupp Mill, where he produced cloth-making and farm machinery, and steam engines. His works also manufactured Edwin Budding’s lawnmower – the world’s first.

James Ferrabee, son of John Ferrabee (an engineer from Thrupp) and his wife Esther, was baptised at St Laurence on 13th December 1818. He established the Phoenix Iron Works foundry at Thrupp Mill, where he produced cloth-making and farm machinery, and steam engines. His works also manufactured Edwin Budding’s lawnmower – the world’s first.

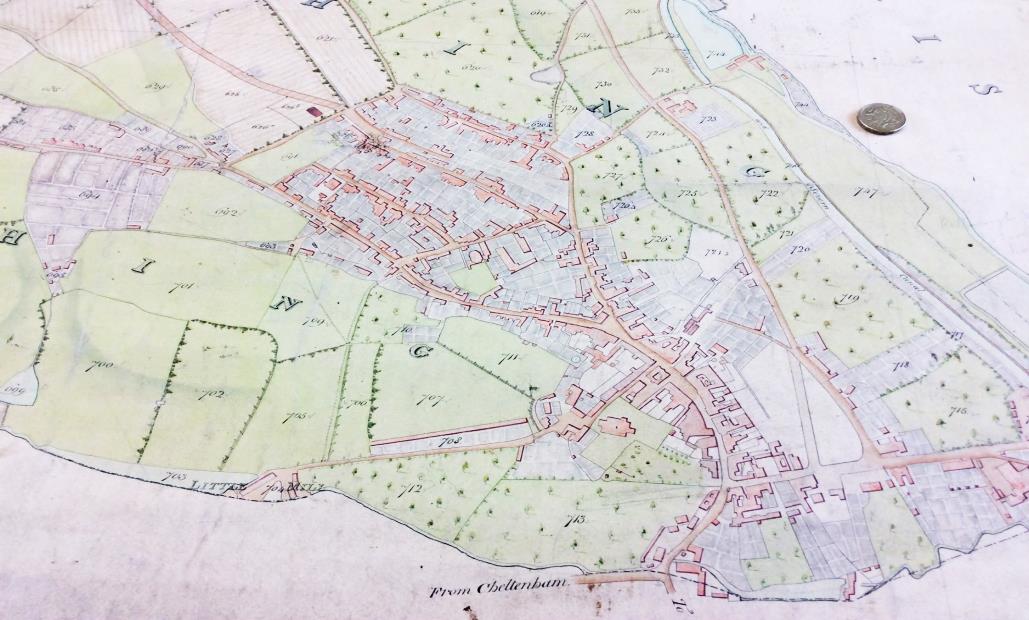

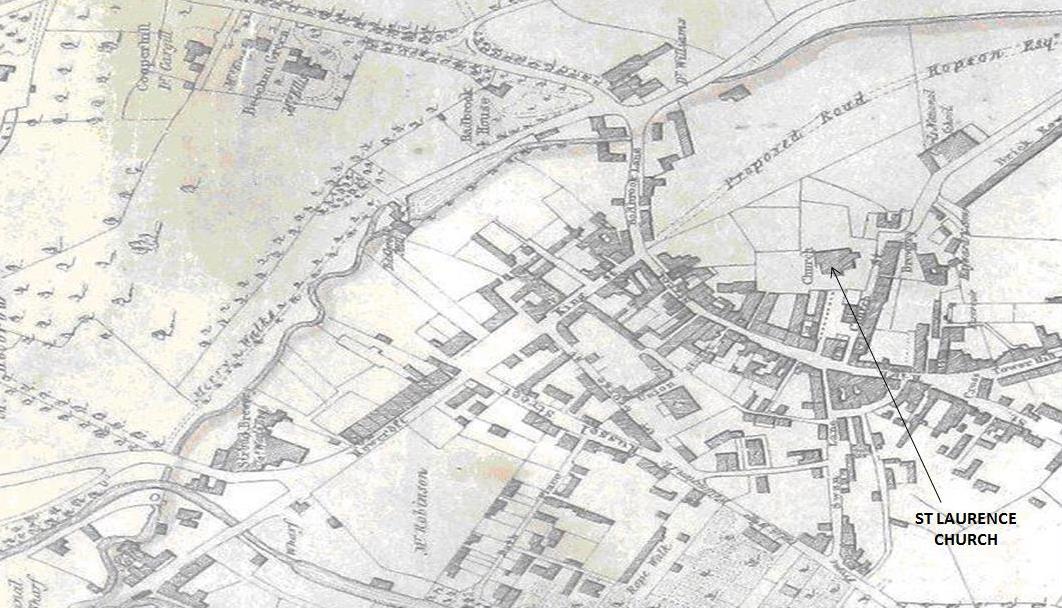

Baker’s Maps

Perhaps amongst the church’s most impressive artefacts in Gloucestershire Archives are two huge hand-drawn maps by Charles Baker, a surveyor, cartographer and architect from Painswick. One shows the Paganhill area and dates from 1819; and the other shows the tithings of Upper Lypiatt, Lower Lypiatt and Steanbridge, and dates to 1820. The period between 1800 and 1840 was a period of rapid growth and expansion thanks to the local cloth manufacturing industry, and the town doubled in size. This growth was evident on Whit Sunday, 10th June 1832, when rev John Williams baptised 113 children at the church. The task occupied him from 12 noon until 5pm. The street pattern of Stroud town centre as we know it today was emerging, and considerable building had taken place. At the same time, reform of industrial practices saw the disappearance of the old cottage industries and the concentration of weaving and textile production into a few large mills served by the advent of steam power.

Perhaps amongst the church’s most impressive artefacts in Gloucestershire Archives are two huge hand-drawn maps by Charles Baker, a surveyor, cartographer and architect from Painswick. One shows the Paganhill area and dates from 1819; and the other shows the tithings of Upper Lypiatt, Lower Lypiatt and Steanbridge, and dates to 1820. The period between 1800 and 1840 was a period of rapid growth and expansion thanks to the local cloth manufacturing industry, and the town doubled in size. This growth was evident on Whit Sunday, 10th June 1832, when rev John Williams baptised 113 children at the church. The task occupied him from 12 noon until 5pm. The street pattern of Stroud town centre as we know it today was emerging, and considerable building had taken place. At the same time, reform of industrial practices saw the disappearance of the old cottage industries and the concentration of weaving and textile production into a few large mills served by the advent of steam power.

The Stephens Family Vault Uncovered

In 1833, workmen were employed to repair the floor over the Stephens family vault near to the current Stephens Memorial. On taking off one of its large covering stones, they exposed a coffin which had been covered with crimson cloth, and richly ornamented with brass. They baled out the water in which the coffin lay, and forced open and removed its lid. They then cut out the upper half of the lid of an oak shell within, together with the corresponding portion of an inner lead coffin. This done they unfolded a winding sheet, and found a corpse which had on a cap, a crimson neckcloth, and a shroud of fine linen plaited on the breast. The body lay, for two-thirds of its depth, in a dark liquid, and was so well preserved that it clearly showed the features of a young man. Becoming concerned about further meddling with the corpse, the workmen hastily replaced all the parts of the coffin, and laid, on the lid of the outer coffin a loose plate of lead which had been found lying on the inner one, crudely inscribed “Farrington Stephens, aged 20 years”. Farrington Stephens was the eldest son of the last John Stephens of Over (Upper) Lypiatt, and was buried on 11th February 1775. When the floor of the new church was again being levelled in 1868, the covering stones of this vault were once more removed, in the presence of the curate John Badcock. But it was found that the air admitted in 1833 and the intervening 35 years had done their work: the head and chest had disappeared, having sunk into the dark liquid that remained in the lead coffin.

In 1833, workmen were employed to repair the floor over the Stephens family vault near to the current Stephens Memorial. On taking off one of its large covering stones, they exposed a coffin which had been covered with crimson cloth, and richly ornamented with brass. They baled out the water in which the coffin lay, and forced open and removed its lid. They then cut out the upper half of the lid of an oak shell within, together with the corresponding portion of an inner lead coffin. This done they unfolded a winding sheet, and found a corpse which had on a cap, a crimson neckcloth, and a shroud of fine linen plaited on the breast. The body lay, for two-thirds of its depth, in a dark liquid, and was so well preserved that it clearly showed the features of a young man. Becoming concerned about further meddling with the corpse, the workmen hastily replaced all the parts of the coffin, and laid, on the lid of the outer coffin a loose plate of lead which had been found lying on the inner one, crudely inscribed “Farrington Stephens, aged 20 years”. Farrington Stephens was the eldest son of the last John Stephens of Over (Upper) Lypiatt, and was buried on 11th February 1775. When the floor of the new church was again being levelled in 1868, the covering stones of this vault were once more removed, in the presence of the curate John Badcock. But it was found that the air admitted in 1833 and the intervening 35 years had done their work: the head and chest had disappeared, having sunk into the dark liquid that remained in the lead coffin.

John Wood's map of Stroud for the Company of the Proprietors of the Stroudwater Navigation, 1835

An Australian Bishop

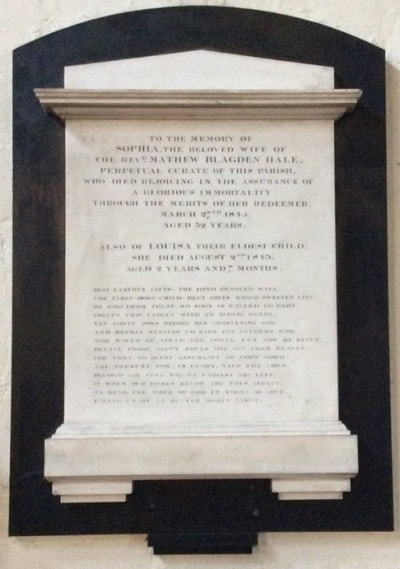

Mathew Blagden Hale was born in 1811 at Alderley in Gloucestershire. Educated at Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucester School, and Trinity College, Cambridge, he was ordained in 1836 and became permanent curate of the church in 1839. However, the death of his wife, Sophia, and of his mother both in 1845 severely affected his health, and he resigned his post. Two years later, Augustus Short, Bishop of Adelaide, invited Hale to become archdeacon and examining chaplain for South Australia. Eager for missionary work among the Aboriginals, he accepted and on arrival in Australia he was given charge of St Matthew's in Kensington, and soon afterwards of St John's in Adelaide. Hale was subsequently appointed the first Bishop of Western Australia in 1857, and later Bishop of Brisbane. He finally retired in March 1885 and returned to England. He died in Bristol in 1895.

Mathew Blagden Hale was born in 1811 at Alderley in Gloucestershire. Educated at Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucester School, and Trinity College, Cambridge, he was ordained in 1836 and became permanent curate of the church in 1839. However, the death of his wife, Sophia, and of his mother both in 1845 severely affected his health, and he resigned his post. Two years later, Augustus Short, Bishop of Adelaide, invited Hale to become archdeacon and examining chaplain for South Australia. Eager for missionary work among the Aboriginals, he accepted and on arrival in Australia he was given charge of St Matthew's in Kensington, and soon afterwards of St John's in Adelaide. Hale was subsequently appointed the first Bishop of Western Australia in 1857, and later Bishop of Brisbane. He finally retired in March 1885 and returned to England. He died in Bristol in 1895.

Left: Mathew Blagden Hale, about 1859

Right: Memorial to Hale’s wife Sophia (died 1845), and daughter Louisa (died 1843) on the west wall of the church

Right: Memorial to Hale’s wife Sophia (died 1845), and daughter Louisa (died 1843) on the west wall of the church

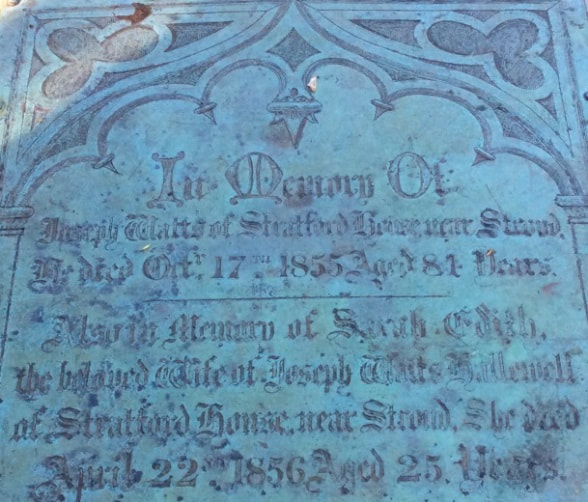

Joseph Watts, Brewer

Joseph Watts (1772-1855), was proprietor of the Stroud Brewery Company, and owned Stratford House, having bought it in 1819 from Samuel Wathen of Woodchester. Jospeh’s daughter Martha (1801-1846) married Edmund Gilling Hallewell, and upon Joseph’s death in 1855, her son (Joseph’s grandson), Joseph Watts Hallewell (1823-1891) inherited the house. Joseph Watts Hallewell was educated at Rugby and Jesus College, Cambridge, and was later a magistrate for the County of Gloucester. After inheriting Stratford House in 1855, he focused his interest on the extensive grounds, and changed the estate's name from Stratford House to Stratford Park - hosting the 1870 Gloucestershire Agricultural Show. He died at Stratford Park in 1891, and the Park was sold to George Holloway MP. Joseph Watts Hallewell’s first wife was Sarah Edith Berrie (1831-1856), and she is buried at St Laurence with her husband’s grandfather. Stratford House is now Stroud’s Museum in the Park.

Family historian Laurence Hallewell has kindly supplied some additional information about the family:

"Joseph Watts Hallewell was also MP for Stroud and chairman of the local Conservative Party. Emund Gilling Hallewell was the son of a clergyman at Boroughbridge, in the West Riding, and had come to Stroud around 1800, and I was brought up to believe that “Squire Hallewell” was a distant relative. The facts were otherwise, but I was in middle age before I did some research in Stroud and found out the origin of this fond family myth, which I hope you will find of interest. My own great-great grandfather, John Hallawell, a bookbinder, had also arrived in Stroud “from the North country” (probably Saddleworth, also then in the West Riding) in 1800. His son Samuel was a house decorator, frequently in financial difficulties from alcoholism. On one such occasion in 1841 his wife Mary had to take her three month old son into Stroud Workhouse.She, being a dissenter, had to have her son baptised as a condition of admission. Out of malicious black humour she gave her name as Martha Hallewell and his as Joseph, so she could claim that “Martha Hallewell and son Joseph were now living in the workhouse.”"

Joseph Watts (1772-1855), was proprietor of the Stroud Brewery Company, and owned Stratford House, having bought it in 1819 from Samuel Wathen of Woodchester. Jospeh’s daughter Martha (1801-1846) married Edmund Gilling Hallewell, and upon Joseph’s death in 1855, her son (Joseph’s grandson), Joseph Watts Hallewell (1823-1891) inherited the house. Joseph Watts Hallewell was educated at Rugby and Jesus College, Cambridge, and was later a magistrate for the County of Gloucester. After inheriting Stratford House in 1855, he focused his interest on the extensive grounds, and changed the estate's name from Stratford House to Stratford Park - hosting the 1870 Gloucestershire Agricultural Show. He died at Stratford Park in 1891, and the Park was sold to George Holloway MP. Joseph Watts Hallewell’s first wife was Sarah Edith Berrie (1831-1856), and she is buried at St Laurence with her husband’s grandfather. Stratford House is now Stroud’s Museum in the Park.

Family historian Laurence Hallewell has kindly supplied some additional information about the family:

"Joseph Watts Hallewell was also MP for Stroud and chairman of the local Conservative Party. Emund Gilling Hallewell was the son of a clergyman at Boroughbridge, in the West Riding, and had come to Stroud around 1800, and I was brought up to believe that “Squire Hallewell” was a distant relative. The facts were otherwise, but I was in middle age before I did some research in Stroud and found out the origin of this fond family myth, which I hope you will find of interest. My own great-great grandfather, John Hallawell, a bookbinder, had also arrived in Stroud “from the North country” (probably Saddleworth, also then in the West Riding) in 1800. His son Samuel was a house decorator, frequently in financial difficulties from alcoholism. On one such occasion in 1841 his wife Mary had to take her three month old son into Stroud Workhouse.She, being a dissenter, had to have her son baptised as a condition of admission. Out of malicious black humour she gave her name as Martha Hallewell and his as Joseph, so she could claim that “Martha Hallewell and son Joseph were now living in the workhouse.”"

"In Memory Of

Joseph Watts of Stratford House near Stroud

He died Octr 17TH 1855 Aged 81 Years

Also in Memory of Sarah Edith

The beloved wife of Joseph Watts Hallewell

Of Stratford House near Stroud She died

April 22ND 1856 Aged 25 Years"

Joseph Watts of Stratford House near Stroud

He died Octr 17TH 1855 Aged 81 Years

Also in Memory of Sarah Edith

The beloved wife of Joseph Watts Hallewell

Of Stratford House near Stroud She died

April 22ND 1856 Aged 25 Years"

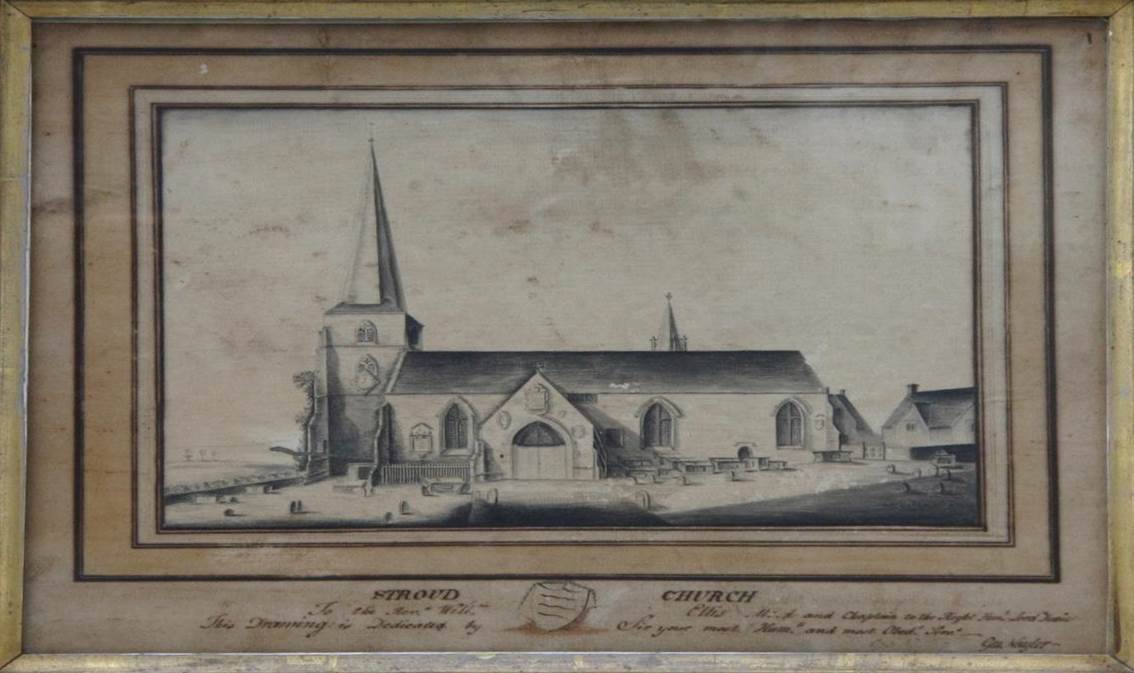

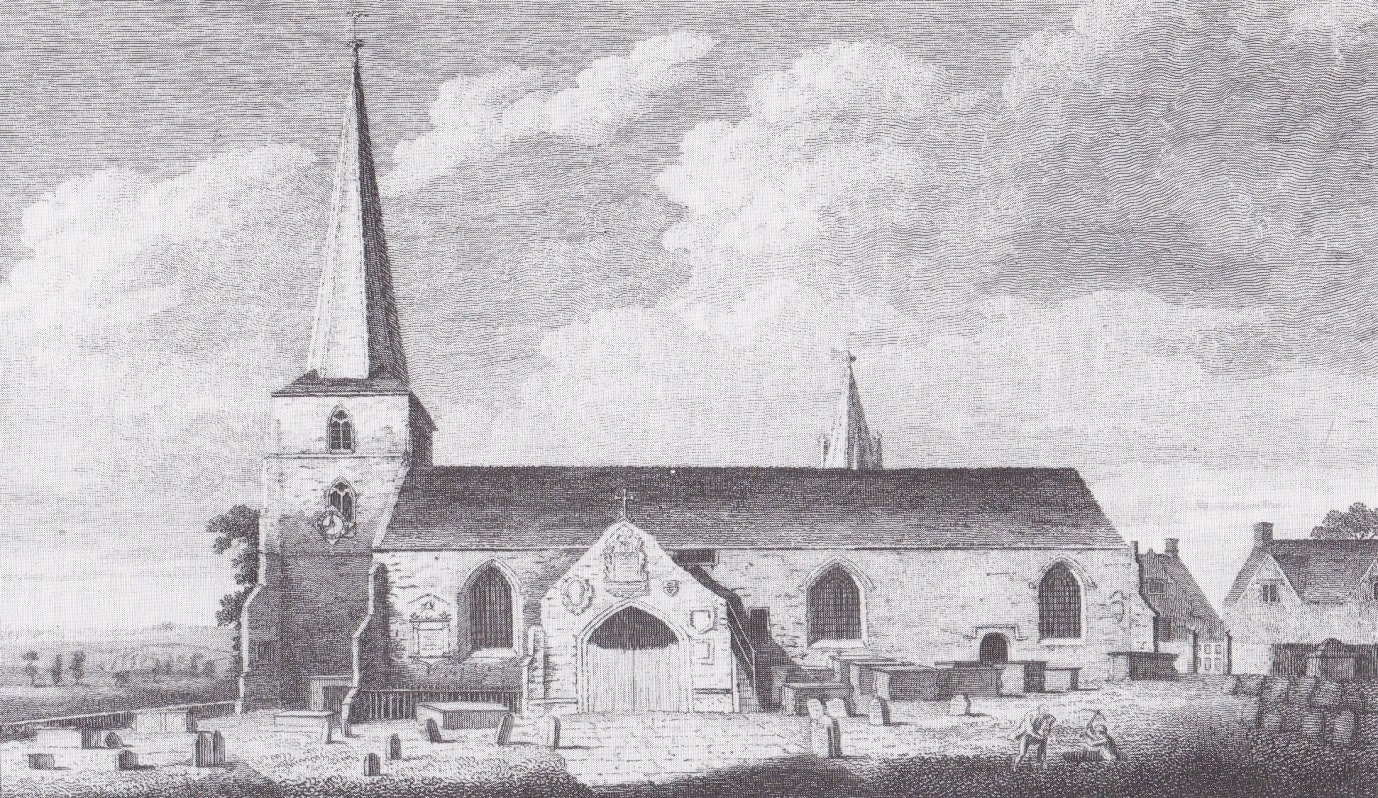

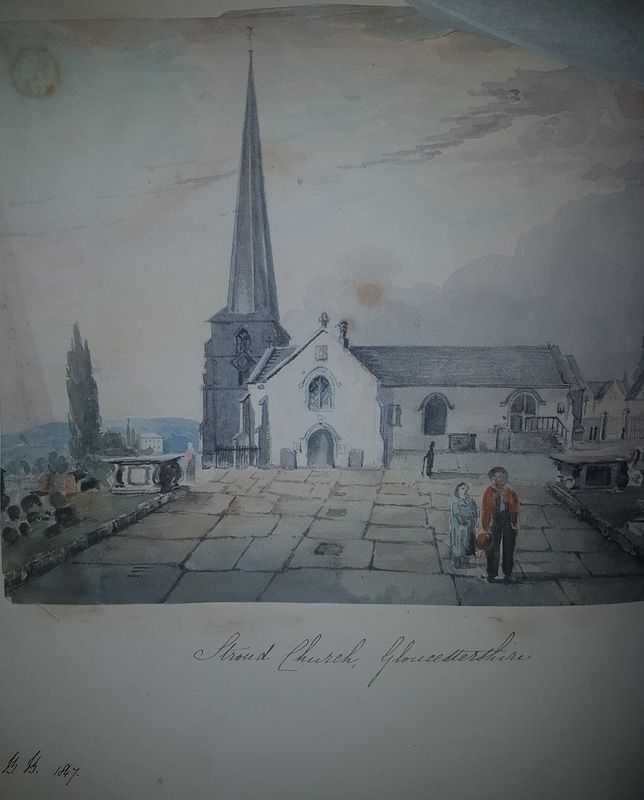

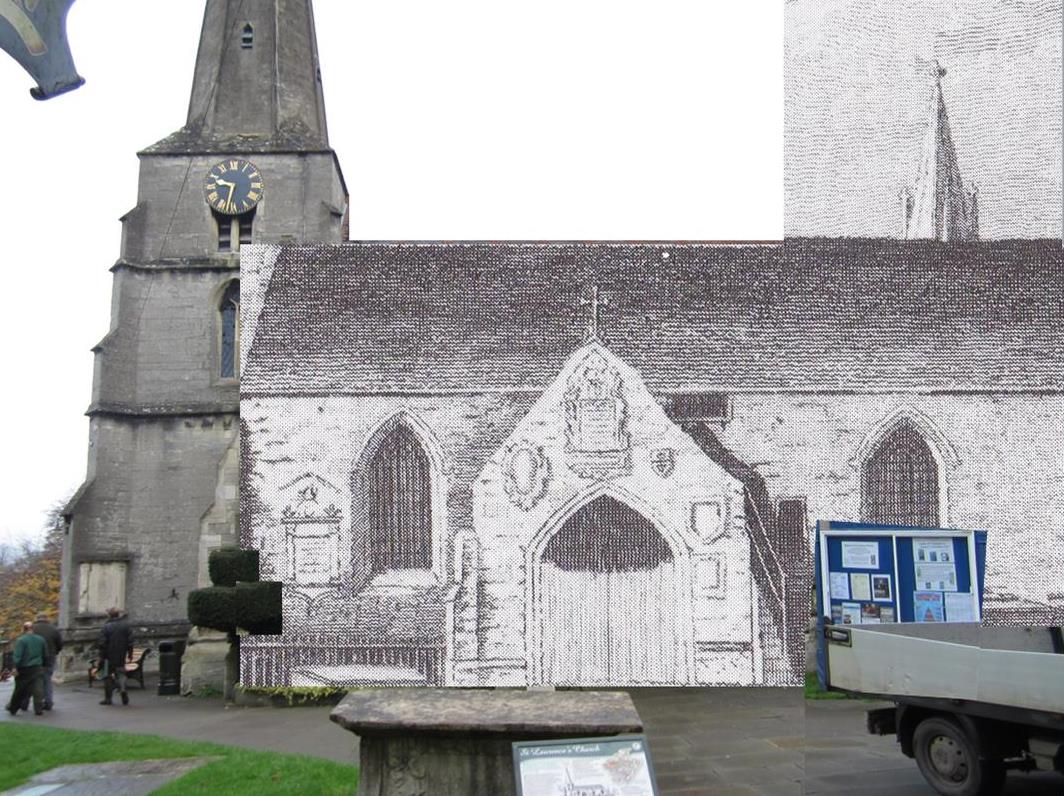

St Laurence Church - Drawing by Alfred Newland Smith, Stroud, 1860

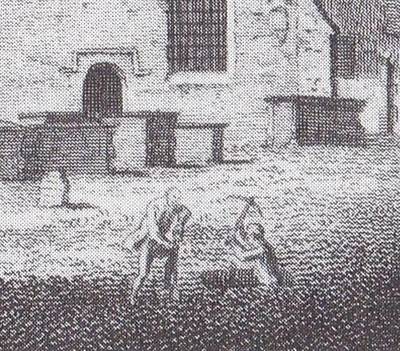

Then and now: the South Porch in 1860 (left) and 2015 (right)

These two brass plates were screwed to the floor of the vicar’s vestry. Below the vestry was the heating boiler room and the plates had three levers with which the vicar and churchwardens could control the boiler. They are now on display on the south wall of the church.

Interior views of the original church just prior to its demolition in 1866

Top left: West end of the nave showing the original organ in its gallery

Top right: East end of the nave and chancel

Bottom left: West end of north aisle

Bottom right: West end of south aisle

(Photographs copied by Alfred T Ford, from originals in the possession of a Mr C W Holland)

Top left: West end of the nave showing the original organ in its gallery

Top right: East end of the nave and chancel

Bottom left: West end of north aisle

Bottom right: West end of south aisle

(Photographs copied by Alfred T Ford, from originals in the possession of a Mr C W Holland)

Plan of the church just prior to demolition in 1866, superimposed on a plan of the current church

Reconstructed views of the original church on today's street scene - showing what it would look like today if the old church hadn't been demolished and rebuilt

If you have any stories, information, documents or photographs about St Laurence that you would like to share with us, then we would love to hear from you